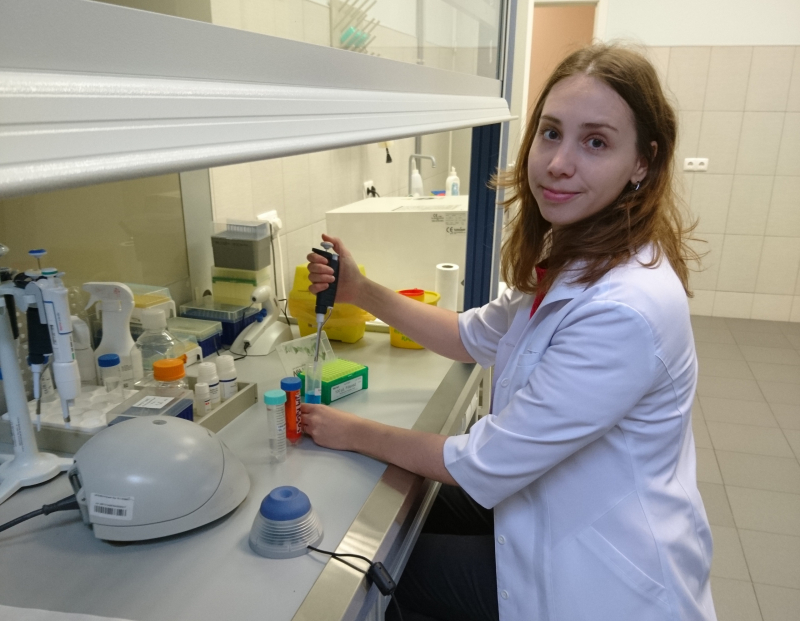

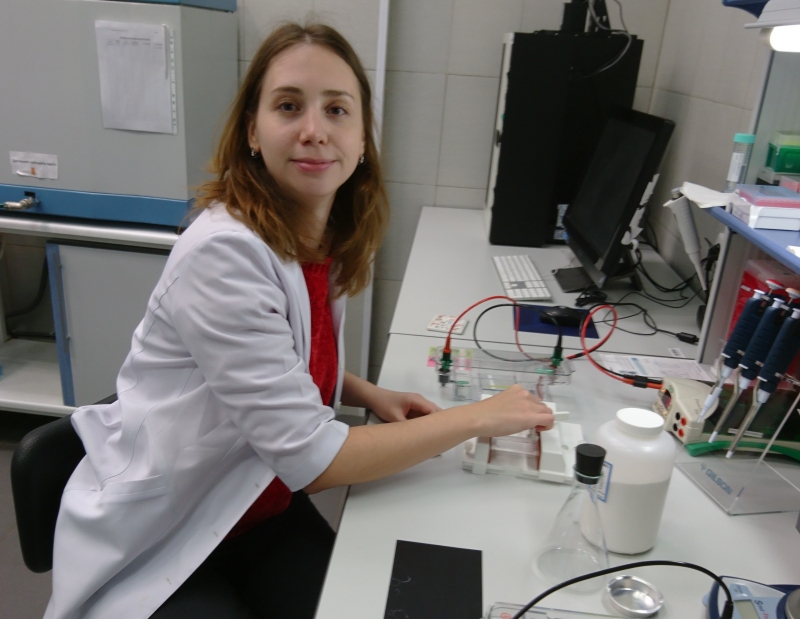

Annually, ITMO University invites leading and promising scientists from all over the world to bring their projects to life in St. Petersburg as part of the ITMO Fellowship and Professorship program. Among them is Anna Zhuk, a bioinformatics researcher specializing in mutation studies. ITMO.NEWS contacted the scientist to learn about her project, impressions of ITMO University, as well as how she came into bioinformatics.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself? Where are you from, where did you study?

I studied at the Lyceum No. 419 in St. Petersburg’s Petrodvortsovy District, after which I enrolled at St. Petersburg State University’s Faculty of Applied Mathematics and Control Processes, which I graduated from with honors as a qualified mathematician and system programmer.

What attracted me most when I was applying there were the words “applied mathematics” in the name, I thought that the focus would be predominantly on using maths for solving applied tasks, for modeling processes in the field of physics, biology, and chemistry. But it didn’t quite turn out to be that way – we mostly did fundamental math and it wasn’t very clear how to use this knowledge for applied tasks.

After getting my diploma I decided that I wanted something closer to real life and enrolled in Master’s studies at the Faculty of Biology. I had a purely biological topic that had no relation to mathematics, the only thing that came in handy was my knowledge of statistical methods, used to check statistical significance of obtained biological results. Just imagine – a mathematician that had never been in a biological laboratory before, had never held a dropper in their hand, found themselves in a situation where they had to carry out experiments on mice, dissect them, extract their liver and subject it to various molecular and genetic methods. I really liked it, I found it so exciting! I have to give credit to my scientific advisors, who weren’t afraid to let me in the lab and taught me a lot. Of course, I lacked some basic knowledge in biology, and as my Master’s allowed me to take additional courses, I put the main emphasis on molecular biology and genetics. As a result, I got my diploma with honors and applied for PhD studies at the Faculty of Genetics and Biotechnologies with Elena I. Stepchenkova and Sergey G. Inge-Vechtomov as my scientific advisors.

I studied under them, won grants and participated in internships, went to the University of Nebraska’s Medical Center in the US, which we collaborated with and I still actively interact with now. After completing my PhD studies, I enrolled in postgraduate studies at St. Petersburg State University’s Center of Genome Bioinformatics to specialize in the field of bioinformatics and genomics under the guidance of Stephen O’Brien.

What kind of research specifically did you conduct?

During my Master’s, I started to study the mechanisms of mutagenesis in different objects. That is, I studied how mutations occur, how some mutations turn into others, how primary DNA damage occurs which is not yet a mutation, and how this transformation is brought about. For example, we simulated stress in mice examining its contribution to the violation of genome stability, for example, whether stress can affect the activity of liver enzymes and lead to activation of mutagens, i.e. substances which by themselves are not mutagens but can turn into ones in the case of a certain enzymatic treatment that occurs in the liver.

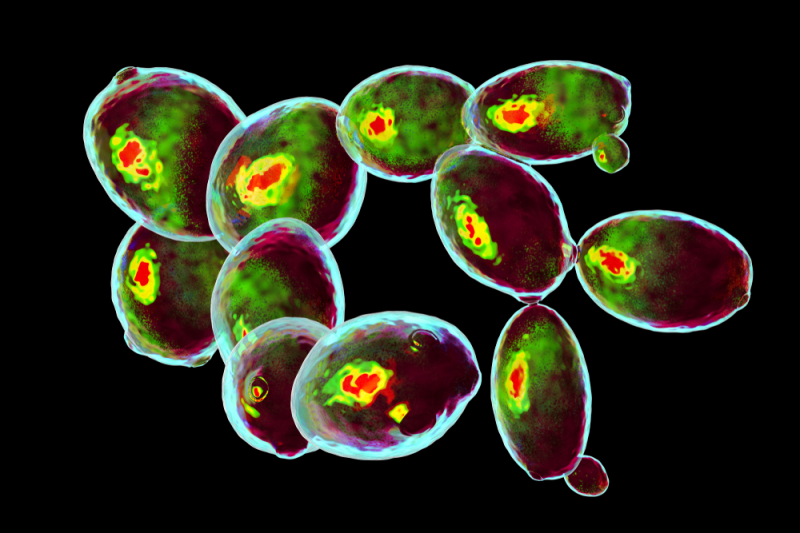

During my PhD, I continued to study how mutations occur, but on a different object – yeast. We tried to determine whether primary DNA damage, even before it becomes mutagenic, can impact the body, and looked into which kinds of mutations they can cause. Apart from that, we developed a special yeast-based testing system which can be used in genetic toxicology – a branch of science that aims to detect potential mutagens and carcinogens in the environment, which is needed for preventing their harmful impact on human health.

And what research did you carry out later, when working with Prof. O’Brien?

In my postgraduate studies, I wanted to focus on bioinformatics, which is why at that point I mainly worked with human genomics. Among other things, I participated in the Genome Russia project, where we analyzed genomic data and developed a database containing genetic variations specific to Russia’s population.

On bioinformatics

As far as we can tell, bioinformatics is a very young science, especially in Russia…

Yes, back in 2003, when I was applying to the Faculty of Applied Mathematics and Control Processes, bioinformatics was unheard of. Moreover, when I completed my Specialist degree in 2008, it was hard to find bioinformatics – otherwise I wouldn’t have gone over to the Faculty of Biology. But there was no such specialization back then, it was only in 2011 – 2012 that the first majors, courses and programs started to appear.

You were trained both in math and biology before you switched to bioinformatics, do you see yourself more as a biologist working with mathematical methods, or an informatician working with biological data?

I’ve been doing biology for a long time now – over ten years, which is why I’m more of a biologist than a mathematician. Of course, my math education helps me in my work, allowing me to solve the tasks that require mathematical knowledge faster. When biologists assign bioinformaticians with some task, they don’t always understand how specialists in the field of data analysis think. The mix of two fields of knowledge helps me to better interact with both.

With that, when you analyze biological data, it’s important to not just follow some pipeline or algorithm – you have to understand how this data will be used afterwards, how accurate they turned out to be in terms of the biological task set.

On ITMO University

How did you come to ITMO?

I was invited by Prof. O’Brien, under the guidance of whom I worked at St. Petersburg State University, after he went over to work at ITMO. I met Vladimir Ulyantsev, he told me about the ITMO Fellowship and Professorship program. I submitted a project there and won.

What are your impressions of ITMO?

There are lots of young specialists among the staff, research is conducted in modern fields. ITMO opens a lot of opportunities for young scientists to develop both in research and in teaching.

What was the project you submitted about?

It was on comparative genomics of the Saccharomyces yeast. Yeast is one of the most widely used model objects in biology. It’s used to study different molecular aspects of eukaryotic biology, for example, to study mechanisms that ensure genome stability, as well as to model human diseases, for example, various neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Pakrinson’s disease, as well as type 2 diabetes, hereditary metabolic diseases associated with metabolic disturbance in amino acids and many others.

Yeast is used not only for scientific purposes but also in biotechnology, to synthesize medications and proteins, and the industry, to manufacture food products such as beer and wine. Yeast was the first eukaryotic organism whose genome was fully sequenced. Yeast is very diverse. Using new-generation sequencing and bioinformatic methods, we conduct comparative analysis, searching for mutations that can explain specific phenotypic features. Detailed examination of the yeast genome allows us to correctly interpret biological results obtained on its basis and expands the opportunities for its application in biotechnology.

But how can yeast serve as a model for animals and humans?

As the body of biological data increased, it became clear that basic cellular mechanisms, as well as functional pathways, were fully or partially preserved throughout evolution. Yeast allows us to study many fundamental mechanisms. People are not yeast, but they have many homologous genes and similar principles, for example, how DNA synthesis or repair of DNA damage occurs. Based on the data obtained on yeast, we can make assumptions about how these processes work in humans, and continue to dig in this direction.

Not everything can be studied directly on humans. With yeast, we can modify something, turn something off, or, vice versa, amplify it.

Of course, this isn’t a direct analogy, extrapolating the results of such data on humans always raises certain questions. But this is an opportunity to understand some fundamental mechanisms humans may also have.

What results do you hope to achieve in the course of working on this project?

The study of how genetic variation is transformed into phenotypic diversity is one of the key topics in biology. Comparative genomic analysis allows us to expand our knowledge in this field. The project’s results will be published in journals and presented at conferences. For example, recently we’ve submitted a publication in which we described the mechanism of cellular adaptation in the case of the DNA synthesis system malfunction and identified the genetic component involved in this process.

On hobbies, the pandemic and plans for the future

How do you relax? Do you have any hobbies you pursue outside of science?

The further I go, the more time science takes up, this is practically 24/7 work. Working on a project, it’s hard to even switch to something else. Before, I used to snowboard, mountain climb, and ride a motorcycle. Now, I decided to give standup paddleboarding a go – this is the kind of a board on which you sail using a paddle to propel yourself forward. This helps to unwind and switch your mind to something else.

How do you spend your time in self-isolation?

I have a lot of data to analyze. This data was used to prepare papers, in this time we’ve submitted three papers to various journals – this took up a lot of time.

You’ve been in the US many times, and also traveled to Europe. Do you ever think about working at a laboratory abroad?

I don’t rule this possibility out, a scientist’s career often requires mobility.