Why did you choose to work at ITMO?

I came to St. Petersburg in early 2013, right after graduating from Zhejiang University. With this foundation in place, I started a Master's at ITMO, changing my major to learn more about photonics and physics. Later, I got a PhD and now I'm working as a researcher in the Microwave Division in the Faculty of Physics and Engineering. Upon my arrival in Russia, I already decided to stay for my PhD, so it sounds like quite a consecutive period, but I didn't expect to stay after that. Everything just evolved naturally, and I’m very happy with it.

Which changes at ITMO have been the most notable for you?

When I first came here we weren’t even a Faculty, but a Metamaterials Laboratory. After several years of development, we got stronger and became the independent Faculty of Physics and Engineering. At the beginning of my career, there was a very small group of researchers, about 30 people in total, and now we’re a 500-person organization. I’m glad I’ve witnessed it become such a big institution through all the stages of creation and development.

Considering my personal impact, back then I was the first international student at the lab and the English-speaking environment wasn’t very developed. Since I came here without knowing any Russian, people had to speak English to me. I guess this accelerated the process of both my adaptation and my colleagues’ skills enhancement. Now we have a lot of international students but for me things have changed — I speak Russian more than English since that was my goal. If you don’t speak Russian, it’s hard to survive outside the lab.

What is the technology you are working on? How can it change the world?

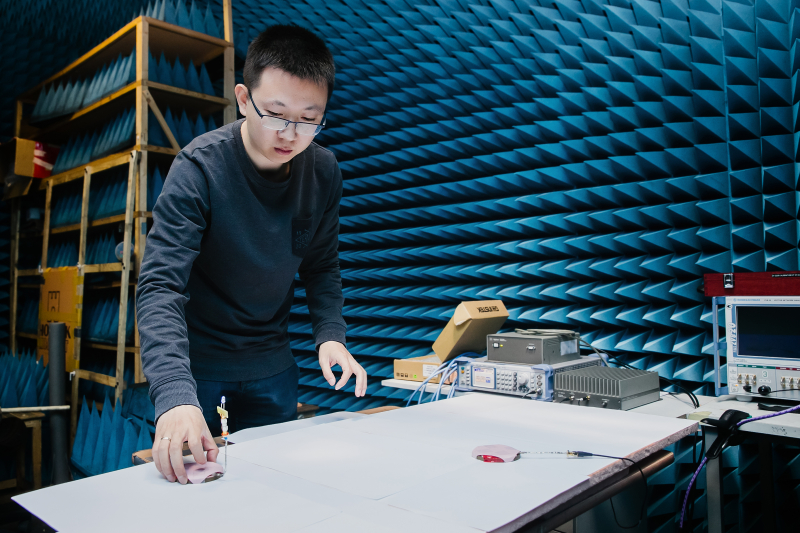

We’re developing the technology of wireless power transfer — a very promising invention that will greatly improve our lives. It was the topic of my PhD thesis, and now we continue our research in the lab. At the current stage, we're working on the proof of concept of novel ideas brought from new findings in other fields.

In terms of technology, our mission is to develop a charging system that allows you to charge your devices unnoticeably — just like when you use Wi-Fi, you don't have to care where you sit or where you go. Charging is important, but we’re mostly concentrated on energy, and our ultimate goal here is to develop different wireless charging systems that are free from charging cords. This can be implemented in different scenarios: for example, you can put your device to be powered on a charging table, or you can embed your charger in the wall that will follow the trace of your device and focus the energy there.

This subject is interdisciplinary — we’re working on this project not fully from an engineering point of view, but also from a physical one, so we need to take into account modeling, experiments, measurement, and other aspects. Fortunately, we have a lot of genius physicists and engineers in our Faculty with whom we can consult and collaborate.

What do you think makes a good scientist?

In my opinion, the key trait of a prominent scientist is the passion to find the truth. To move the world, it’s not a good way to adapt to everything and let it happen randomly. You need to be curious and always try to find what goes wrong. Of course, experiments can prove your expectations, but they are unexpected results that are more precious as they inspire you to generate new ideas. Secondly, I think of logic as more of a necessity without which you just can’t continue any research. Also, you need motivation — it’s not a big deal to cope with your work if you're into it. You naturalize science like you eat or breathe and it becomes an indispensable part of your life.

After such a long time in Russia, is there anything you couldn’t get used to?

I’ve been here for almost eight years and that’s more than a quarter of my life — I’ve finally adapted to everything. I’m basically half-Russian at this point. I’ve mastered the language and got accustomed to cultural features. What’s more important, my family is in St. Petersburg — I live with my wife, who’s also from China and is a PhD student here, and our kid.

Could you give some advice to everyone who struggles to learn Russian?

For the first three years, my language was developing slowly because I was pretty much relying on English. As a result, Russian was like noise to me, but my mind stored information unconsciously and after enough accumulation I found myself understanding more and more.

I’d recommend spending as much time as possible with the Russians, putting yourself in a local environment from the very beginning. I give big credit to my classmates. Besides their assistance during the studies, we played board games together, and that helped to improve my language proficiency significantly. I don’t have to do it anymore, but I also used to watch movies in Russian every day. I remember the first series I watched was Kukhnya (“Kitchen”).

Do you have time for hobbies?

I like different kinds of activities — basketball, swimming, but my favorite sport is billiards. One good thing in my lab is that my colleagues, who're strong scientists, are interested in it as well. Once, at the first METANANO conference in Anapa, I came across a billiards table and decided to take advantage of it. It was during lunch when my colleagues saw me playing and joined me. At that time I didn't speak Russian well so this established a bridge between us, it was an exciting experience. Now we play billiards regularly.

What are your plans for the future?

Beyond the project I'm working on, I would like to maximize my experience and make full use of the knowledge gained through the years here — improve my Russian and help to accelerate the development of my scientific field. Born in China, I also speak Russian and English. By this, I hope to contribute to relationships between China and Russia in different aspects, not only in science.

Check out more international stories and also follow us on Facebook and Instagram.