Many 17-year-olds still don’t know what they plan to do with their lives when they’re asked to choose a career. What was that like for you? Did someone help you make that choice?

This was a choice I made on my own; I wanted to become an engineer since I was in school. It’s really hard to choose a specific calling when you’re 17, but I went with what I know I like. I’ve always been into physics and it was always a subject that came easy to me. And besides, everyone in my family is an engineer.

I come from a small town in the Astrakhan Oblast. In school, I participated in every competition and contest that I could. I think that helped me do better on my Unified State Exam.

Why ITMO?

I applied to many universities, of course, including MIPT, Bauman Technical University, and others. But I ended up choosing ITMO because I wanted to come to St. Petersburg. I’d been there before and I was charmed by the city’s history and atmosphere. As someone from a provincial town, visiting this museum-city was a memorable experience.

Did you know right away what you were going to do after university?

I was involved in a lot of extracurricular activities at ITMO, doing comedy, setting up events, contests, working on the student council, doing photography for ITMO’s Media Center and even hosting my own show on Megabyte student radio. But I had always wanted to work in my chosen field. In my third year, I started looking for work. After my fifth year, I did an internship in Krasnogorsk. And that’s where my career began.

You’ve worked in both academia and the industry. What made you choose the latter?

I settled on industry work when I was doing my Bachelor’s thesis. It was largely practical and revolved around optical surfaces. It so happened that my academic advisor had his own business and he often involved students in solving some of the tasks they had, which gave us an opportunity to work on real projects.

I got to work on a spotlight projection system that emitted light over a distance of about 2 kilometers. But the issue was that the reflecting elements would overheat and flake off. We had to find a way to make them withstand high heat. We did some tests, found a solution and it went into production.

I dabbled in writing scientific articles, but realized that it just wasn’t my thing: I’m interested in the practical results, it’s important for me to see my skills put to use. My Master’s studies only reinforced that feeling. After graduating from ITMO and moving to Moscow, I began my PhD research at Bauman Technical University; within the first year, I was fully convinced that industry work, not research, was the right choice for me.

How did you end up moving to Moscow?

The Krasnogorsky Factory, where I work, had great offers for young specialists. It’s a major enterprise and I had the opportunity to go work there right after finishing my studies. You can even bring your family with you. It’s too bad that I had to leave St. Petersburg and leave many friends and acquaintances behind, but it’s possible that I’ll return there someday.

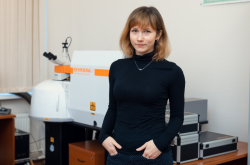

The Krasnogorsky Factory has been a legendary place since the Soviet times. These days, it’s part of the Rostec state corporation and creates optical devices for space exploration, satellites, photography and medicine. What do you do there?

I work at the Department of Optical Technologies and the Lens Assembly Bureau. I work with engineering designs, draw up technical documentation for lens assembly, and help supervise the production process. The factory makes different kinds of lenses, both special-purpose and for civilian use, including lenses for cameras. For instance, our factory makes the stock Zenitar 35mm F/1.0 lens for the Zenit-M camera.

Many professionals are saying that in the recent years, a new generation of engineers failed to replace the previous one. For a long time, factory work wasn’t very “hip” among young specialists. Is this still true today? Has anything changed?

In general, the optics industry is becoming younger, and it’s happening quite fast. At our factory there are plenty of staff aged 30-35, even among the senior staff. I can’t say the exact number, of course, but there are indeed a lot of young people today who choose factory work. I think this is because there’s no better place to get practical experience.

There are many highly qualified experts here who have been working since the Soviet times, even, and they share their experience with us. The Krasnogorsky Factory, for instance, has a mentor system. When I first came here, I was assigned a mentor, who was also my boss. He answered any questions I had and used practical examples; although you can just as well ask any person and they’ll help you out.

Of course, I’d like it if qualified professionals were given support appropriate for the Moscow living standards. There are better financial opportunities at private companies, but they have their own downsides, too.

People have been talking for some years now about the issue of the disconnect between universities and the industry, the lack of practical training and project work. Is this a relevant issue in your industry? If so, how do you think it can be solved?

If we’re talking about optics, we must keep in mind that this is an ancient science; fundamental discoveries that change the entire perception of the field aren’t as common here as, for instance, in IT. That’s why fundamental training remains always relevant. It all depends on how well you studied.

Secondly, universities today are indeed largely disconnected from what’s happening in the industry. The solution is to have more partnerships between universities and companies that would let students come in and experience real work in a serious environment. That way you’ll have graduates who are not only knowledgeable about theory, but also capable of real work. I think it would be appropriate to start these things in the third year of Bachelor’s studies, which is when students are given more specific subjects and when they begin to understand why they’ve been learning these things all along.

What requirements for specialists of your profile does the industry set today?

The big one, I believe, is the will to learn; companies that operate in a narrow field of expertise have experts who are ready to teach the young and pass the necessary knowledge unto them. If you already have any experience at that point, like I did, it gets much easier.

In optics, you have to keep learning and never stop. Even though it’s a fundamental science, there are new technologies and equipment, too. There’s no shame in mimicking the leaders and using their achievements; what’s shameful is using the same old tech and the same old tools. Which is why you absolutely have to always keep up with the latest developments.