You are a graduate of the Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences, where you studied science communication and bionics, and have an impressive research record that includes a number of successful projects in Europe. How did your acquaintance with ITMO start, and why were you interested in joining the university?

ITMO University’s Master’s program in science communication and the program I studied on back at the Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences are very similar in terms of their structures, though the contexts they operate in couldn’t get more different. My alma mater gave me a strong methodological basis for my line of research; I also participated in a range of conferences and studied different aspects of science communication on the global level. My main research focus is communication in fundamental sciences, particularly fundamental physics.

My first acquaintance with ITMO dates back to 2016 when Dmitry Malkov and Daria Denisova, the respective director and deputy director of Science Communication Center, came to Germany. From then on, I’ve been following the projects by the Center’s staff with great interest and admiration. The work they do as pioneers in the field of national science communication is very hard and important. I’m glad to have become a part of it and hope that the knowledge and experience I’ve obtained in Europe will be of service to the Center’s cause.

What will you be working on at ITMO University?

I’m to help students with their research, and also with honing their methodological skills. I don’t position myself as an expert, but hope that my experience will help them avoid certain methodological mistakes.

At the moment, I offer regular consultations to one of the students whose thesis topic is close to mine, which was measuring the effectiveness of one of the two exhibitions organized by CERN. This student is a Master’s student of the science communication program, Daniil Sharov, who’s now in Shanghai coordinating the Magic of Light exhibition (you can learn about it in this article by ITMO.NEWS).

Apart from this, I’m also familiarizing myself with the work of the Center to then join the staff in the projects they’re doing.

Now you’re busy working on a large-scale project for CERN. Could you tell us what that’s about?

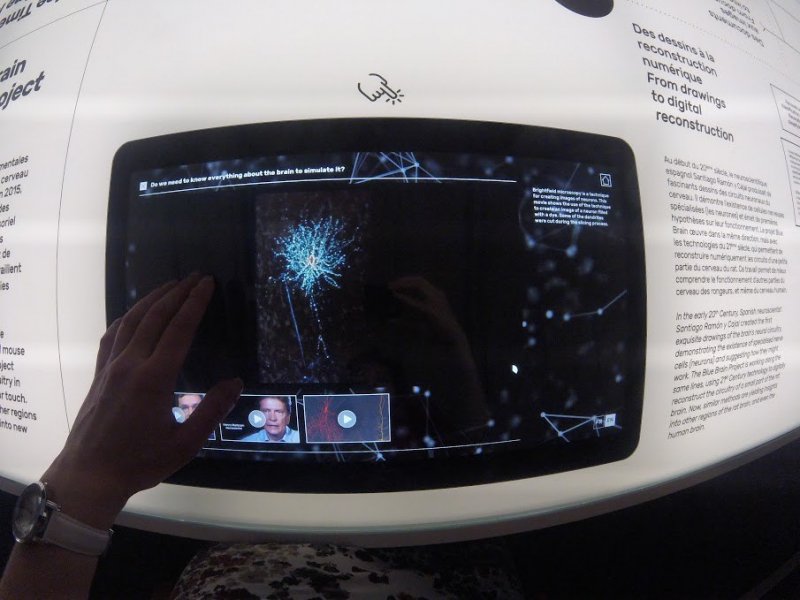

I first came to CERN in 2017, to do an internship aimed at studying its staff’s attitudes to science communication as a specific theoretical model. The following year, I returned to CERN to do some research for my thesis. I was measuring the effectiveness of Microcosm, one of CERN’s regular exhibitions, and made a number of findings that would be useful for different fields of science communication.

It has to be mentioned that CERN does do a lot in terms of science communication, by organizing exhibitions, working with the local population, coordinating online communications and implementing a variety of educational programs. They put a lot of resources into what they do, but it’s difficult to evaluate how effective all these projects are, because for them, it’s a different kind of work, and very demanding at that. So the question of developing such an evaluation process popped up, and I was offered to lead the work on that.

The project I’m working on now is dedicated to identifying the effectiveness of communications aimed at live interaction with the general public. These include exhibitions, tours, and other events held by CERN, one of the largest-scale ones being the CERN Open Days, which are to take place on September 14-15 this year. This event is a result of the meticulous work a large number of CERN’s staff has been doing over the course of the last year and a half. One of my main goals is to understand what kind of output they’ll get.

Far from being easy, this task demands a certain level of methodological expertise in the field of social studies, and also a high degree of objectiveness. There are lots of risks of the findings becoming biased or erroneous, so this work calls for a detached, outside point of view, which I hope my research will provide.

How do you plan to go about your work?

This task is first and foremost a research one, and thus will be conducted in full compliance with all academic and methodological guidelines. I will be closely cooperating with practicing communicators here at CERN as well as colleagues from ITMO University. I think that we struck a perfect working balance to ensure that our joint work will be equally beneficial to all sides involved.

The project has only just started, so the work I’m doing now is largely preparatory: we have to decide on research objectives, go over heaps of relevant literature, prepare and test the tools for garnering data. These tasks imply active collaboration with other research groups at CERN, especially ones in charge of putting together the impending CERN Open Days event.

What specific methods will you use in your work? What kind of data do these require?

The methods I’m going to use are both qualitative and quantitative. If and when applicable, the same concept will be measured from different sides and with different tools, to lower the underlying margin of error. For example, if we talk about audience engagement, we have to start by operationalizing this concept because though everyone talks about it, but few actually know what it means. Also crucial at this stage is to decide exactly what indicators will be attesting of changes in the audience’s level of knowledge of, or attitude to CERN and science and general.

Right now I’m planning to conduct a series of surveys and possibly also use the method of observation. But the final decision will depend on the type of research questions we’ll go for, and also on the technical and administrative limitations we’ll be faced with. The surveys will encompass the audience of the events hosted by CERN, and also other people who are yet to become their participants. Researching the latter group is especially important to how СERN plans its communications and future events.

The other crucial category are tourists. Some of them travel from the other end of the world just to visit one of CERN’s exhibitions, whilst others come to the region, find themselves 2km away from CERN and have zero interest in visiting. That’s the case I’m most curious in studying.

What results do you plan to achieve? In what way will they be useful to both sides of the project, CERN and ITMO University?

I think that it’s the studying of the people who have never been part of science-pop events that could prove especially useful. This is a well-known problem: scientific centers and museums are for the most part attended by people with an already high level of knowledge or strong interest in the topic. But how do we diversify that audience? And does it need to be diversified in the first place? These are very important questions.

To that end, I want to form an understanding of social and economic barriers that could be standing between CERN and its audience. These findings will be of use to different scientific organizations, such as CERN and ITMO, as they try to engage as large a number of people as possible.

Apart from that, all of the tools and methodologies developed and examined in the process will of course come in handy in any other science communication projects. This field can’t develop without research, as the practical aspects must be substantiated with theoretical knowledge. This is why I plan to share my developments and implement them in other projects I’ll be part of.

What formats of scientific events aimed at the general public do you deem the most promising and why?

There are lots of different formats in Europe, from science festivals to science fairs and markets. There are science centers, science museums, and even science cafes. Most of these have become a regular practice in the eyes of science communication professionals.

As a researcher, I try to stay unbiased in how I view all of these formats; the risk of introducing error to our research is already high enough. Of course, you can’t help but be attracted to something new, something that has never been done before. But this leads to the situation where standard approaches to transferring scientific knowledge are pitted against newer ones, positioned as more “open” and innovative, more active in involving the general public in scientific processes.

I must admit that I still don’t have everything figured out, and that’s why I’m so interested in what this rather abstract idea of engaging “regular” people in research would look like on practice. And also, whether it is right to look for ways of implementing this idea in the case of fundamental science.

Based on your experience and insight, what types of science pop events could be applied in Russia?

Now we’re witnessing active professionalization of the science communication field. What this means is that every exhibition or display, not to mention museums and scientific centers as a whole, is a result of the work done by big teams of people, each bringing their own experience and expertise to the table. The professional community is growing, and so are the numbers of works published and events organized. It would be great if theorists and practitioners in Russia had a readily available opportunity to participate in international conferences, for them to always be in the center of the latest debates and developments. I think what’s most important is to find a good balance between being open to what’s developed abroad and keeping the focus on what’s created at home, within the Russian scientific ecosystem.

European initiatives often put a premium on interacting with local communities, and operating a Western set of values, which isn’t always easy to envisage working in the Russian context. But what if it would? That’s why my take on the question is, we have to watch and research.