Why did you get specifically into physics?

They say you typically become interested in physics as a small child. I’ve always been fascinated by nature. I tried to explore everything around me – flowers, trees, bugs, butterflies, stones – before I could even walk. When I was around four or five years old, I was very impressed when my dad showed me how friction creates sparks and that you can grow crystals from a salt solution. That’s when I acquired my interest in physics.

Plus, my grandfather graduated from Leningrad State University’s faculty of physics and taught this subject to students of the Military Artillery Academy during the Siege of Leningrad. They’d studied for just three months and then left for the battlefront. I show my students the books they used to study. My grandfather worked as a lecturer for his entire life and was admired by his students, but unfortunately he died an untimely death and I didn’t have a chance to talk to him. But one might say that interest in physics runs in our family.

I was very eager to start studying physics at school. This subject fascinated me from the start. Then, in ninth grade, a new teacher joined our school – Galina Stepanova, an acknowledged St. Petersburg methodologist. She taught physics and supported my interest in this field. I knew that I would apply for the faculty of physics at Leningrad State University. Studying there was my dream.

After graduation, you had several options, like teaching at school or working at a lab or a factory. Why did you choose to teach at a university?

I’m not going to lie – being a school teacher is quite a tough and thankless job. In the ‘90s, there was no demand for young scientists. I wanted to work at a university because I thought that being a lecturer would suit me and allow me to both work and take care of my family. I had several options but I chose ITMO University, largely because I was impressed by its professor, Nikolai Yaryshev, who at the time headed the department of physics. “He’s a wise and kind person,” I thought when I met him. This made me want to work with him and that’s how I joined ITMO. About 28 years later, I’m still here.

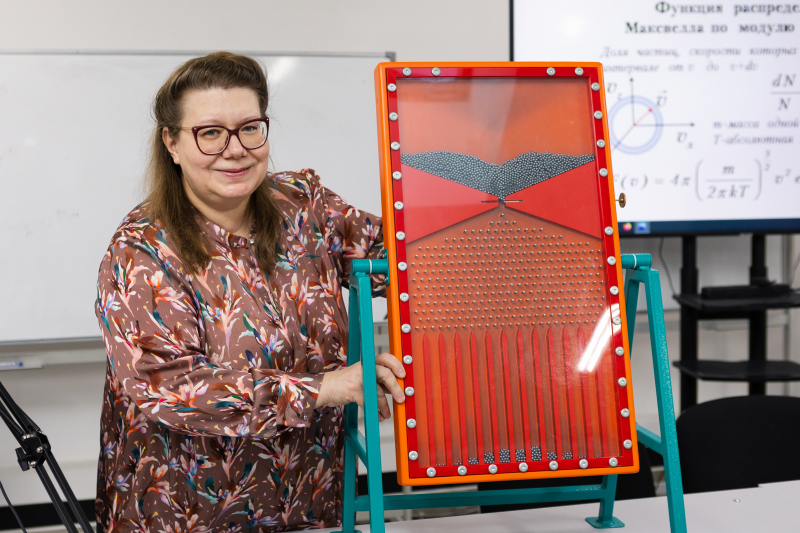

Svetlana Kurashova. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

Do you somehow apply the teaching approaches of Leningrad State University at ITMO?

The university opened a path for us, both in terms of career and life in general. First off, I would like to mention my lecturers from Leningrad State University. I’m really grateful to them. They taught us not only how to be a good specialist but also how to grow as a person. When I entered the faculty of physics after graduating from school, I was amazed by the way they treat students. My classmates and I knew that we were loved, respected, and appreciated. This was very uplifting. I won’t ever forget the way Evgeny Butikov, a lecturer who greatly influenced the way physics was taught in the Soviet Union in the second half of the 20th century, always looked us straight in the eyes and smiled, so we knew he liked us, believed in us, and expected us to solve his hard tasks. This made us want to not disappoint him. His lectures were fascinating, too. I’m really glad that I had an opportunity to learn from this talented lecturer and a great person. For a long time, he used to work with ITMO students, too.

Prof. Nikita Tolstoy, a son of the writer Aleksey Tolstoy, also taught at our faculty. We loved the way he used unconventional examples to explain the nature of physical phenomena. Sometimes we felt like he was being a little superficial – that’s how easy it was to study his subject – but later on, I realized that it was great, he just had a way of making the learning process fun and comprehensible. I still tell his funny stories to my students.

Naturally, I’m trying to recreate the LSU atmosphere and approach to students. For example, Svetlana Nazarova, our lecturer of English, called us “bunnies” – we felt really loved and happy during her lectures. Now I call my students “kittens” and they like that too. Surprisingly, Svetlana Nazarova taught me Russian, too – thanks to her, I knew how to make reports and look for sources. Kindness and the ability to teach something that goes beyond your subject are very valuable.

But we weren’t spoiled at all – it was really hard to study. After the first exam session, every third student was expelled and I think that’s okay – because higher education isn’t for everyone. We wanted to study and intuitively felt that these are prominent specialists teaching us – this made us happy and motivated. Our faculty’s hymn included the words “Moon is staring through the window but the student’s still awake, buried in books…”

Do you have any teaching secrets or rules?

I don’t have any secrets, just the truth you need to realize: you’ll be a good lecturer if you’ll treat your profession seriously and feel respect and love for your students. You either feel that or you don’t. My parents and I felt loved during our studies and now we can pass it on. When my mom was studying at the faculty of philology at Leningrad State University in the post-war years, many students didn’t have fathers, so lecturers tried to somehow provide this fatherly love to them. Some even invited them over to their houses in the countryside to discuss literature and just hang out.

In my first few years at ITMO, it was sometimes hard to decide what to do with students who didn’t want to study. I wanted to punish them somehow but always remembered our philosophy lecturer Vyacheslav Grechanyi and his academic papers, in which he wrote that kindness is only real when it’s meant for everyone, not for specific people. This helped me find an approach to lazy students.

You should make a distinction between how you feel about the level of students’ knowledge and about them as human beings. You can love them but be strict with them at the same time. I try to make them realize that studying is important for them and we won’t encourage laziness, but still, we love them, believe in them, and hope that they’ll do good.

Svetlana Kurashova. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

Are you more of a “carrot” or “stick” person when it comes to teaching?

One cannot exist without the other. That’s how it was when I was a student, too. Our mathematics teacher used to make us retake tests 3 or 4 times, each harder than the other. We knew it was a demanding task, but we loved him and never doubted that he truly loved us. That’s just how it works.

Sometimes, humor helps: you can tease a student and they’ll start paying attention. There are different methods that you have to use. A colleague of mine had a student from Kazakhstan who caught COVID last spring. He went back to his home country, didn’t do anything, and ended up failing the class. So, he now had to take an exam with a special expert committee. He got scared and called me to ask what he should do. I asked him whether he felt embarrassed about letting down a great teacher who was reprimanded because of him. As a result, he spent an entire week studying and got a “good” grade on his exam. That worked! Sometimes even we’re amazed how they’re essentially still children. But teachers bear a great responsibility. After all, students are sincere people and they can sense kindness and even more so – injustice.

I hope that they’ll remember us the way we remember our own teachers, but even more strongly I hope that they’ll be great people. To me, teaching is a source of joy.

How do you know if a course is successful?

It’s easy. First off, it’s the atmosphere that exists in the classroom. It’s when you feel that they understand the material and their interest gives you energy. In this way, we’re like actors; but being an actor is easier because they do exciting things on stage while viewers just observe. We, on the other hand, talk about things that aren’t always that interesting while students have to put in work, as well. Secondly, you can always tell by the way a student answers questions, or even the way they make mistakes. It’s one thing when they haven’t prepared and another if they did, but haven’t remembered it all – and you can feel the difference.

To make classes more lively and exciting, I try to use presentations, movies, and games. Sometimes you can just take a short break during the lecture to let them get some rest while you share facts about scientists. Those people shouldn’t just be portraits on the wall to the students. For example, the great British physicist Michael Faraday, being not that wealthy himself, vehemently declined an offer, for which he would’ve been paid well, to develop chemical weapons that would be used against the Russian army during the Crimean War. That right there is a lesson in morals.

Winners of the 2021 ITMO.EduStars contest. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

What has changed since you found out you won the contest?

I put a lot of energy into my work and try to do my job well, so, of course, I was very pleased to hear such praise of my work. I realize that it puts more responsibility on me. To be fair, I’ll admit I never expected to win. I didn’t catch on to the fact that this was a contest and not just a performance review. It was a lot of joy: when I received my award, people came up to congratulate me who I didn’t even know. Unfortunately, among the winners there weren’t any of those teachers who have dedicated their whole life to ITMO and whose projects made the university known countrywide. I believe they deserve a special category.

I’d also like to say that the student surveys that were part of the contest are in fact very valuable. I’m still embarrassed about an error of my youth: when I was a student, we held a poll to rank our teachers. We had a column where you had to include your grade on the corresponding subject and the percentage of classes you attended. The lower those figures were, the less weight was assigned to a student’s response. As a result, one of our mathematics lecturers decided not to retire, but a physics teacher, who we judged incorrectly out of our inexperience, left the university.

15 years later, I felt bad about it – and I still do. Only having worked as a teacher for several years have I been able to truly appreciate what a remarkable scientist, wonderful lecturer, and great textbook author he was; he also staged these fascinating experiments that we all loved very much; and that’s not to mention that he once had left his position as head of department to volunteer as a soldier during the war. But he taught us in his old age and could no longer handle the workload. So student feedback is, on the one hand, important, but also can never be absolutely objective – and you must think very carefully about how to properly collect it. If a student did nothing and skipped all their classes, how can they be trusted to evaluate a teacher?

What do you do in your free time?

Unfortunately, I don’t have that much free time. I like gardening and spending time in nature; I love our wonderful suburban parks, especially Pavlovsk. I receive great pleasure from opera and stage plays. If I had to name my favorite operas, I’d go with Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades and Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya. By the way, in the late 19th century the composers Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin fought fervently to make education, including women’s education, more accessible. I would very much love to see our students connect with our beautiful city’s spirit and get to know its museums and theaters a lot better. I think that students feel that they’re surrounded by the magic of Russia’s cultural capital and take joy in becoming a part of it.