As a school student, Anastasia Tukmakova liked physics and especially thermodynamics. That’s why she decided to enter the Refrigeration, Cryogenic Equipment and Life Support Systems studies at ITMO University’s Faculty of Cryogenic Engineering.

During her third year of studies, she realized that she wanted to work with more eco-friendly technologies. Later, she became interested in thermoelectricity and kept working in this field during her Master’s and PhD studies.

ITMO.NEWS asked Anastasia why she decided to work in science rather than in the industry, what the working process of scientists looks like, and what you can learn during internships abroad.

When you applied to ITMO University, did you think that you would work in science? Or did you want to work as an engineer after getting your degree?

I never wanted to become an engineer in the industry. At school I was into physics, especially thermodynamics – it’s a very beautiful science. When I entered the university, I didn’t realize that a major in engineering is not quite about science and physics. Eventually, by my third year of studies, I decided that I was more interested in theoretical, abstract tasks rather than in engineering solutions which could be applied in the industry.

What did you study as a Bachelor’s student?

My Bachelor’s major was related to refrigeration systems. I wrote my thesis about rotary-screw refrigeration compressors. We studied the refrigeration industry, refrigeration systems, and large-scale energetics. After that, I switched to small, solid-state, and eco-friendly devices. I wanted to work with something more environmentally friendly.

I’ve always been interested in alternative energy sources, so in my third year of studies I picked a scientific project related to heat-flow meters and how they can be applied in measurement of thermal radiation in the human body. Then I entered the Thermoelectricity Master’s program, now titled Solid-State Cooling Systems.

You are now a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Cryogenic Engineering. Did you ever think that you would give lectures to students? How hard is it for you?

Of course, I never thought I would become a lecturer. Teaching is quite hard, as it requires a lot of involvement. It goes beyond lecture preparation and figuring out a way to explain everything in an engaging and efficient way. But I actually enjoy it. Sometimes you get inspiration and interesting ideas on how to improve the course. I think I’m growing a lot in this area. I haven’t been teaching for a long time, just for the past two or three years.

Do you give lectures to both Bachelor’s and Master’s students? Is there a big difference?

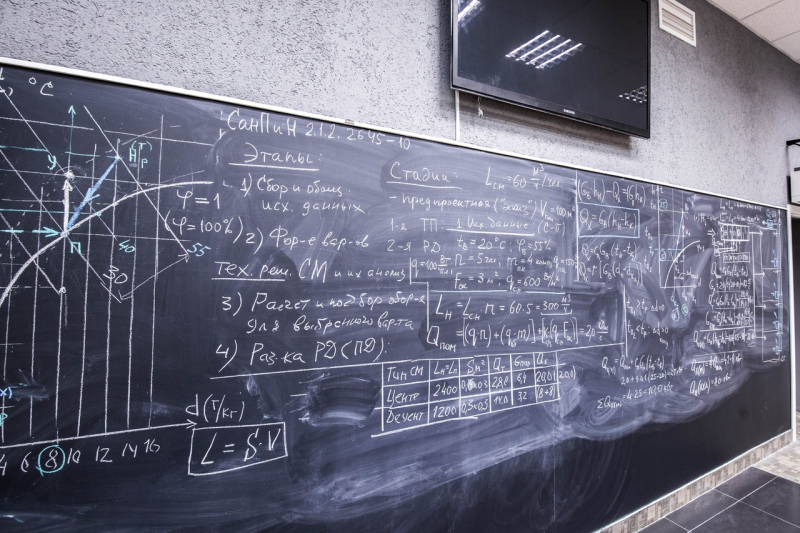

Working with Bachelor’s students requires more preparation. We work on specific tasks with Master’s students and these are the tasks that we are engaged in every day anyway. It goes naturally and easily. General theoretical questions, on the other hand, require more preparation, so it’s much harder for me to work with Bachelor’s students. There’s also more responsibility for the knowledge you give them.

Don’t you and your Master’s students also work on projects together?

Yes, it’s easy to engage Master’s students in projects. For example, two years ago me and one of my Master’s students began to work on a project about modeling the process of creation of nanostructured materials. She helped me develop the model. Together we took part in an international conference on thermoelectricity which was held in South Korea last year.

Together with several Master’s students and the Terahertz Biomedicine Laboratory we also work on a grant from the Russian Science Foundation (RSF). One of the students, Ivan Tkhorzhevsky, helped us with modeling, defended his thesis, and won the contest for the best thesis at ITMO University this year.

This RSF project is one of the most interesting ones we have. We started to work on it last year. At ITMO Open Science, I presented a short paper on thermoelectricity, and my colleague, Elena Makarova, presented a poster presentation on thin-film thermoelectrics. Our colleagues from the field of photonics (from the Terahertz Biomedicine Laboratory) were very interested in our papers. They really liked the idea of using thin films as thermoelectrics because in their field materials with a similar structure – like graphene – are very useful. Our materials were brand-new, so few people had worked with them. That’s how I began to cooperate with the International Scientific and Research Institute of Bioengineering.

You work as an engineer at this institute. Could you tell us what kind of projects you are engaged in?

I work on the modeling of a terahertz sensor. Some of the center’s employees are engaged in film synthesis, and others – in studying the characteristics of materials. My task is to create a model based on what data we have, and see whether a thermal response is possible in film thermoelectrics.

Thermoelectric materials make it possible to generate electricity once a temperature difference occurs in a thermoelectric circuit. Temperature difference creates electrical voltage or electric current. This effect can be used for detection. We decided to create a thermoelectric detector that would be sensitive to terahertz radiation. If the film heats up or changes its characteristics because it interacted with radiation of a certain frequency, then it’s possible to create a sensor.

Judging by the results that we got, the effect really exists. That’s why we want to keep researching this and develop the optimal configuration of the detector in order to get a better response. At the same time, experimenters study various effects that appear on these films under various radiation conditions.

What is your global goal, the main fields in which you work? Do you have a dream project?

The main fields I focus on are energy, energetics, and thermodynamics. People who work in these fields have a common pipe dream – pure energetics: eco-friendly devices, new functional materials, and smart systems. It’s a dream about pure and sustainable energetics.

In general, it’s very hard to come up with a perfect project because your attitude changes each year. The more you work, the more you learn, and the more get surprised about how much stuff is going on around you, how much you can create. All project ideas appear as if out of nowhere. You work, you create, you try new things, and then at some point a new idea is born. I think it’s very hard to plan it, it’s a dynamic process which is hard to foresee.

My task is to learn and to do as much as possible.

You travel a lot as a scientist: you participate in conferences and internships at international laboratories. Did you think that it was going to be like that when you applied for Master’s and PhD studies? Does it correspond to your expectations?

I didn’t really have any expectations because I had no idea what the working process of scientists looks like. Of course, it turned out to be quite complex: there are certain everyday responsibilities and tasks which must be completed even if you don’t feel like doing them. But you get used to it and it becomes normal.

Trips, conferences, and internships attracted me in the beginning. My research advisor had a lot of experience of working with international colleagues. He spent some time working in Korea and traveled a lot in general. So when I decided to work in science, I knew that in the best-case scenario, I would travel the world a lot and it would be fascinating.

Have you ever considered leaving ITMO University and Russia to work at an international university?

Moving abroad doesn’t mean abandoning your university or your country. It’s more about the opportunity to learn something new. International internships are great because you get access to new devices and new people who, perhaps, are doing the same thing as you but using another set of tools. It allows you to meet scientists you never even dreamed of meeting. Sometimes fascinating intersections occur.

For example, this autumn I was working on thermoelectric generators based on new materials in Japan and met a colleague from Austria. Their scientific advisor was working on phase diagrams. I was just getting into that field, too, so they gave me several lectures. It was very helpful. It wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t gone there, it was totally unexpected.

Trips abroad allow you to grow a lot during a short period of time. Then you can come back and apply your new experience in Russia, at your university. Staying in one place is not always a good idea. Lots of experienced people I know have worked in several universities. They had worked in America, in Asia, and then settled down somewhere in Europe. And it’s normal. It gives us an opportunity to broaden our horizons, meet new people, and create interesting large-scale projects. It doesn’t mean you can’t communicate and cooperate with your ex-colleagues.

What are your plans for the future?

My plan for the nearest future is to defend my thesis in September. I will think about what to do in the future later. Right now I’m focused on the defense.

What is your thesis about?

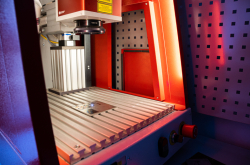

The topic is “Modeling the Sintering Processes of Nanostructured Thermoelectrics”. I’m trying to model thermal and electrical processes which take place when nanopowder is processed. They can’t be observed experimentally. We need to simulate them in order to understand which properties nanopowder will acquire after the processing, so that we could create materials with features that are useful for thermoelectricity.

What advice would you give to those who want to apply for Master’s studies?

On top of studying hard and not missing your classes, I’d recommend trying all kinds of new stuff.

If a student wants to work in science, they should take part in projects, come up with their own ideas, and be more proactive starting from their Bachelor’s studies. Participation in contests, including ITMO University’s ones, and conferences, writing articles, and doing presentations helps a lot. It’s much easier to enter Master’s studies if you have some achievements and a portfolio. You should remember that Master’s studies are more about studying by yourself, about your initiatives, so you should be ready: you should know what you want and why you want it.