You started teaching when you were a student yourself. How did you get this opportunity?

When I was a PhD student, I mainly did research. Once, my colleagues asked me to be a substitute teacher for lab classes. My research topic was very interesting and promising and this helped me to present something new and cutting-edge to the students. The classes were focused on laser radiation and its effect on nanostructured materials and were meant to help students acquire practical skills in nanotechnologies. But most notably, these lab classes later grew into my PhD thesis. This was the start of my career as a lecturer.

At ITMO, teaching is closely connected to your research activities. After I defended my PhD thesis, I started supervising students. For instance, in 2012 Rezida Nabiullina was accepted to ITMO and started doing research under my supervision; this year, she will defend her own PhD thesis. Over the ten years of our collaboration, I helped her reach the same level that I myself was at when we first met.

What do you like most about your job?

I don’t only teach but also work at the admissions offices for Bachelor’s and Master’s programs. The best thing is to witness yesterday’s applicants take my class and then achieve great heights. Some of the students who entered our programs are now leading researchers at international universities. Among them there are several students from the international Master’s program Physics and Technology of Nanostructures – for instance, Nikita Teplyakov, who is now a PhD student at Imperial College London, and Tatiana Vovk, who works at the Institute for Quantum Optics and Quantum Information in Austria. I am glad to see our students grow and I am proud to have contributed to their research careers.

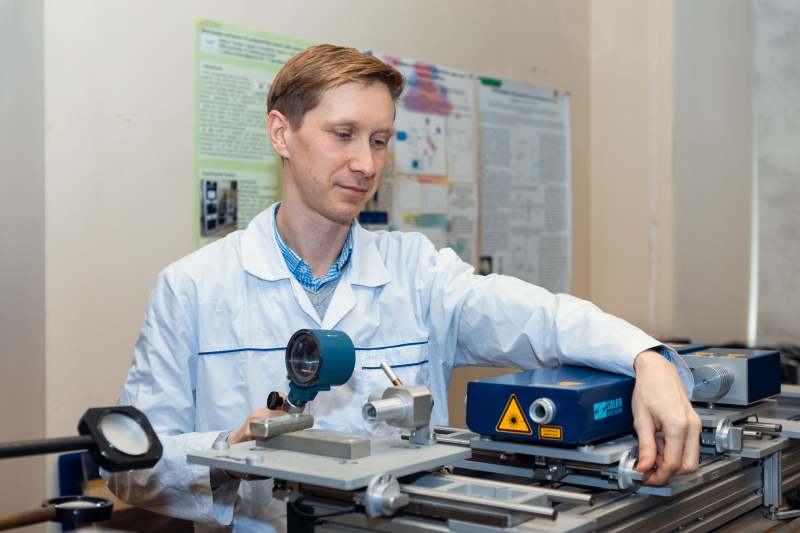

Anton Starovoytov. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

When the pandemic started, you were able to quickly switch to the remote format. What helped you to efficiently teach online classes?

I use Nearpod to host my lectures. It lets me add feedback forms into my presentations. This way, I can implement small tasks, such as tests or open questions, and collect the replies right in the middle of the class. If a student fails to answer, then they’ve lost track of the lecture. I can always track that and that motivates students to listen so that they can answer a question in time.

Actually, I think a great disadvantage of online education is that students lose the necessary hands-on skills. Lectures and practical classes can be held online, but you can’t really do the same with lab equipment. Nevertheless, when we had to move online, I was able to create computational simulations of some equipment in Excel for lab classes on nonlinear optics. Of course, it’s not hands-on work per se, but it still made it possible to create a special simulation to model the way results are generated by actual lab equipment. This way, students could do their lab projects at home and acquire the results that they could’ve produced at the university.

You said that lecturers have to show students different opinions and guide them towards their own solutions. How do you accomplish this in your own classes?

I was talking more about supervising rather than regular lectures because those are more standardized. Unfortunately, there are no ready-made solutions in research. We can find different explanations of the same physical phenomenon in different publications and it’s only through additional research that we can choose one of the options. And students conduct these activities with a supervisor. In other words, supervisors are guides that should help see what versions there are and how to sort them out.

Sometimes it happens that the version we pick isn’t entirely right. In this case, we discuss it with our colleagues. Once, we submitted a paper for publication with one of my students and our reviewers sent it back commenting that our explanation of the discovered physical phenomenon is wrong. As a result, we ran additional experiments and added them to the article.

Such failures happen in research from time to time: we apply for grants and publications, but not all of them succeed. At first, you treat it philosophically and in time you learn to generate many approaches so that you can apply for different projects.

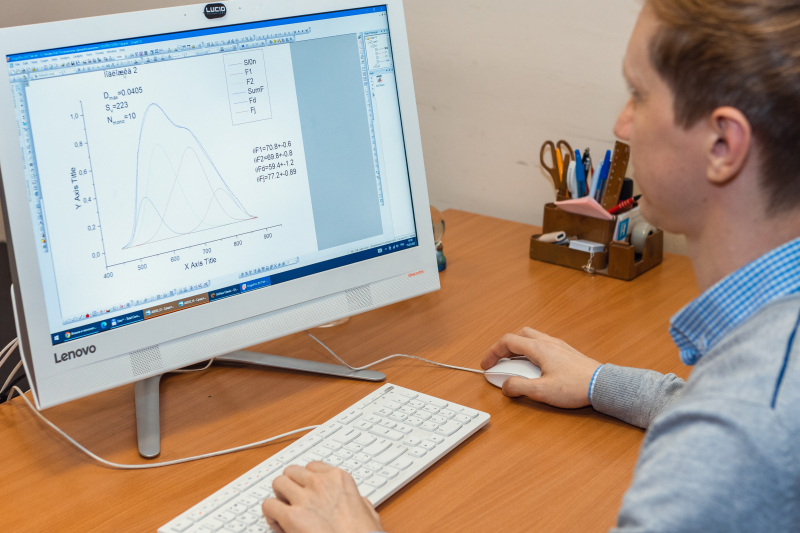

Anton Starovoytov. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

Apart from teaching, you also take part in grants and work at the International Research and Educational Center for Physics of Nanostructures. How do you combine all of these different kinds of activities?

Originally, our center focused on research. Eventually, we implemented Bachelor’s and Master’s programs and so, the center’s researchers started teaching classes, too. They are highly qualified in the subjects they teach and this allows them to help students implement their small-scale research projects as part of larger commercial ones.

Unfortunately, both in teaching and in research you often have to meet deadlines, but there are also relatively quiet times when you can devote more time to one of these fields. I try to organize my work in a way that would allow my students to work on experiments and acquire practical skills. However, students don’t have a lot of experience in analyzing the results they produce and that is when my colleagues and I step in to help them. As for teaching, I have distributed my responsibilities evenly throughout the academic year.

International Research and Educational Center for Physics of Nanostructures. Photo by ITMO.NEWS

You have won several grants for young scientists by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research. What do you think helps your team win various grant contests?

It’s mostly thanks to teamwork, because every team member matters when you submit an application. When you are assembling your team, emotional compatibility plays a major role. It’s important for me that I enjoy working with my teammates and that we can rely on each other. Grants usually last several years and they tend to include a lot of deadlines that have to be accounted for. That’s why we have to have a substitute in case someone falls ill and we should also be able to swap our responsibilities if necessary.

This year, several of the projects that won the national contest for best graduation papers focused on quantum dots. What are the current cutting-edge areas in physics of nanostructures?

That depends on who you ask. Our students’ work is focused on the subjects of our research projects – we apply for funding from the Russian Science Foundation (RSF); the application receives funding if found promising; and then we have a grant project that our students work on. For instance, at the Laboratory for Surface Photophysics we have an RSF grant for studies of chiral plasmonic nanostructures and we encourage students from the Master’s program Physics and Technology of Nanostructures to join it. In other words, we generate promising ideas, but then the foundation chooses which of them to support and funds them. That’s why I think any project has the potential to win. The students that won the best graduation paper contest also took part in projects supported by various grants.

What do you think about the ITMO.EduLeaders and ITMO.EduStars contests?

Many of my fellow teachers won ITMO.EduLeaders and it was interesting to learn more about their projects. The project that I submitted last year didn’t make the cut, so I supported others. I saw how their eyes glowed with ideas and I was happy to see them supported. I think Ekaterina Tyurikova’s project was ingenious and I really liked the ideas presented by Yulia Romanenko and Daria Chirva. I think that they truly deserved to win. Their projects are far from the classic teaching model based on passive 1.5 hour-long lectures that lack interaction. No, they are more dynamic and modern, tailored to today’s students, and, in my opinion, likely to spark interest among them.

Which project have you submitted for ITMO.EduLeaders this year?

I’ve updated the last year’s version of my project Excel Simulations of Physical Equipment for Nonlinear Optics. Lab classes have several issues: firstly, students can usually conduct only one experiment with preset parameters and secondly, the equipment wears down, so it has to be maintained or replaced every once in a while. Virtual simulations allow us to bring down the wear on the equipment while giving the students a chance to run a series of experiments with different parameters.

The majority of the devices that we use, such as spectrofluorimeters, need to be linked to computers and can be controlled remotely. Using Excel, I was able to make a program that simulates that specialized software. Many lecturers and students are experienced Excel users, so it won’t be hard for them to model various physical processes based on the laws of physics. During their lab classes, students run an experiment and see a physical law in action, while the lecturer uses simulation to do the opposite – they describe the law in question with a mathematical formula that has to reproduce a certain result. The simulation accounts for various nuances and measurement errors: for instance, you can model noise or additional physical processes. It all depends on the difficulty level that the lecturer chooses for their students. I think such simulations can complement regular lab classes or substitute them in online learning conditions.

What do you do in your free time?

I stay active – I swim at the pool and take fitness classes. And when we get together with friends, we play board games – my favorite is Carcassonne, not least because I had the chance to visit this town when I went to a conference in the nearby Toulouse. Lately, I’ve also been enjoying painting. I started with paint-by-numbers sets, but after completing the third one, I began painting my own landscapes using YouTube tutorials.