Have you ever tried telling a sea elephant from a giant rock in a photo made by a drone? Or counting the exact number of birds depicted in an image of a small penguin colony? This is no easy task, but it is necessary for understanding how populations of these animals change under the conditions of global warming and the melting of glaciers. It’s impossible to ring and tag every animal, so for the time being placing cameras and using drones in the habitats of the studied animals is the most reliable method.

Then again, small research teams often have limited budgets, and processing huge amounts of photos made during a season can be hard for them. Volunteers can be of help here, providing assistance in identifying animals in photographs, which makes it possible to apply big data methods afterwards. One can become such a volunteer by applying at by submitting an application on the website of Zooniverse, a project launched in 2007.

“The main purpose is to help researchers who have large datasets that they cannot analyze themselves or by using computers only,” explains Dr. Grant Miller, project manager at Zooniverse. “To this end, we enable thousands of volunteers to perform simple pattern recognition tasks on the data. A secondary aim is to break down the barriers between professional research and the general public.”

#flippersfirst!

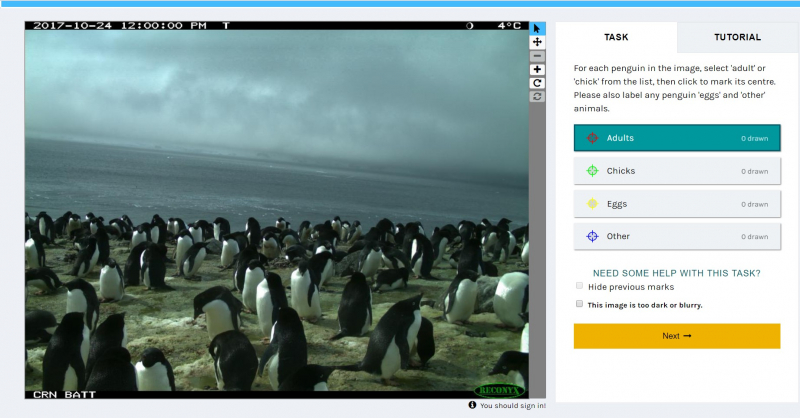

For example, you can help a research team who study penguins. The process itself resembles playing a game or doing wildlife photography: you are given an image made by a stationary camera, and you have to mark adult penguins, hatchlings and eggs with markers of different color. There’s also the fourth marker that you use for marking critters that are dangerous for penguins: sheathbills, giant petrels, great skuas and … humans.

Some photographs take only a couple of minutes to process, as there are just a few penguins on them. Some take about a half an hour, as you need to place about a hundred marks. In these moments, you are starting to understand how limited in resources the scientists who monitor the balance of these fragile ecosystems are. The photos have low resolution, sometimes it’s hard to tell an egg from a stone, but that just boosts your interest. By the way, you don’t have to register to participate, but if you’re willing to share comments about a specific photo with the associated research team, you have to create an account, which takes less than a minute.

After dealing with penguins, you can switch to counting seals. This task is even harder: citizen scientists (that’s how the project’s authors call their volunteers) will have to recognize animals in photos made by drones. What’s more, they’ll have to distinguish sea lions from other seals and mark them with a different color. Doing that from a bird’s eye view isn’t easy, but the organizers give a hint: #flippersfirst! Sea lions have strong front flippers that they can stand on, and can pull their hind limbs underneath their body. Earless seals have short front flippers that hardly touch the ground, and their hind limbs are stretched behind them.

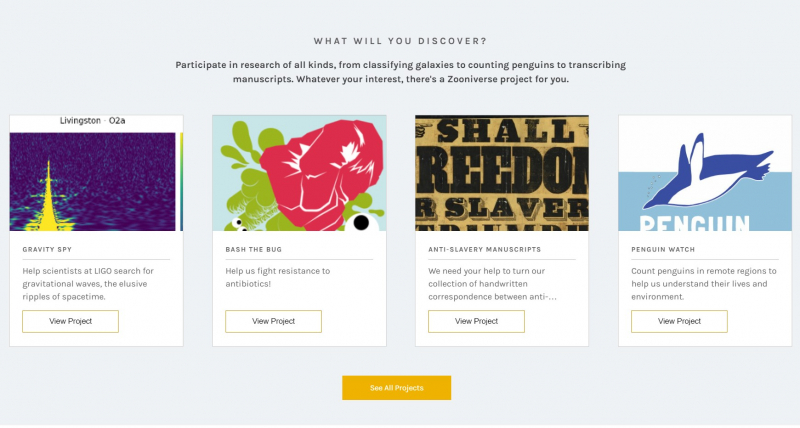

If you’re not really interested in seals and penguins, you can find a different research to your liking.

“We currently have about 100 live projects, and we’ve launched over 250 in total since we began,” says Dr. Miller. “Each project involves a different research team (with a few exceptions). We have worked with researchers from many countries on all continents, including Antarctica. They don’t all study animals, though. The standard way our projects work is that each image is shown to multiple volunteers, so there are multiple answers for each image. The researchers can then aggregate that data to take the crowd consensus as the answer. The researchers download the raw data from the platform, but we also provide some support with data aggregation. Each individual project has a ‘Results’ page where you can check to see the progress of the research and what is being done with the data you have contributed to. We also have a list of publications produced by projects at zooniverse.org/about/publications. Many of these publications list the names of the volunteers who have taken part.”

A good way to fill the time

According to Zoouniverse’s authors, their website’s traffic grew by three times since the beginning of the pandemic. A greater increase has only been registered in 2017, when they spoke about the project on television. Then again, the project’s popularity can well increase even more in the nearest future.

By the way, you can use Zooniverse to not just help scientists but also ask for help with your own research.

“The main way is to try building a project at zooniverse.org/lab. It’s really easy to set up a prototype, and it’s completely free! If you have more questions, you can email contact@zooniverse.org or post a message at zooniverse.org/talk to get answers,” comments Dr. Miller.

You can read more about citizen science projects here.