What do people think about important economic issues? How do their perceptions correspond to reality? While delivering a guest lecture at NES, Stefanie Stantcheva spoke about her latest research and experimental work. She and her colleagues showed how people perceive the economic problems associated with social mobility, immigration, taxation, health insurance, and macroeconomics.

The professor encourages economic researchers and politicians to listen to what people have to say about economic and political changes. According to Stantcheva, if experts do not listen to the voices of ordinary people, then populists will and they are known to oftentimes only promise quick and easy solutions to problems.

“I am studying not only how people feel about such solutions but also how they justify their attitude. That’s why we are interested in mental models that people use while reasoning which solution to support and how we evaluate its effectiveness and fairness. In particular, I analyze tax and trade policy, as well as healthcare,” Stefanie Stantcheva explained earlier in an interview with the newspaper Kommersant.

The methods that the researcher uses in all her projects are large-scale socio-economic online surveys and experiments. When collecting and analyzing people’s views, Prof. Stantcheva suggests paying attention to three key factors: people's perceptions of themselves, other people, the economic system, and politics; their attitude to the concept of justice; and personal economic circumstances.

“Surveys made it possible to see what other data could not: people’s perceptions, attitudes, knowledge, and views. Our goal is to get closer to the intangible. The conventional methods that we used to apply, such as the study of preferences, are no longer enough,” Stefanie Stantcheva says.

The myth of the American Dream

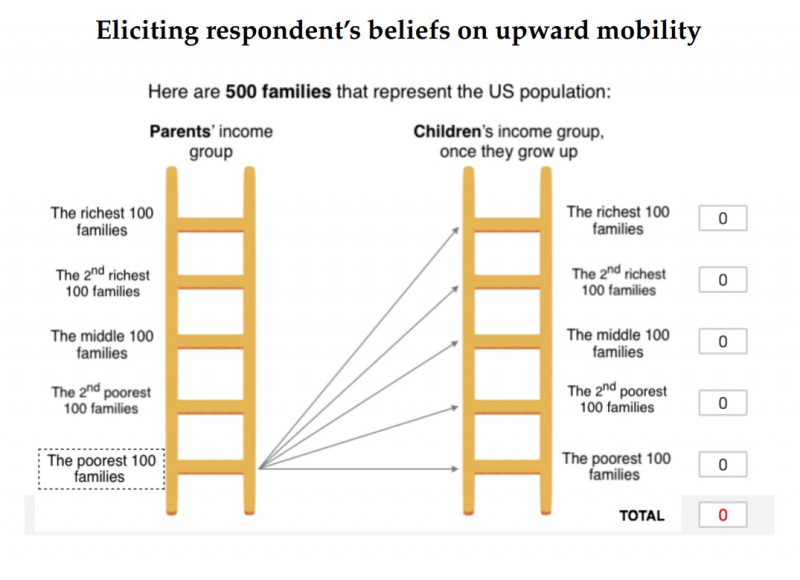

One of Stantcheva’s studies, based on socio-economic surveys, is devoted to intergenerational mobility. By intergenerational mobility, the professor understands the chance for a person from a poor or low-income family to achieve success in society. During the study, scientists tried to trace the relationship between views on mobility with the people’s attitude towards the idea that material goods should be distributed among members of society using social mechanisms or taxation.

Initially, the scientists worked upwards from a stereotype which suggests that there is a specific “American” view of intergenerational mobility associated with the idea of the American Dream as an opportunity to achieve everything through one’s work. As the professor notes, with increasing inequality in the United States, one would assume that ordinary Americans would want to narrow the income gap through progressive taxation. However, Americans still see wealth as a reward for ability and effort, and poverty as the result of failing to seize opportunities.

On the contrary, Europeans believe that the economic system is unfair. In their opinion, wealth is more likely to be associated with family history and inheritance, while poverty is the result of bad luck and the inability of society to care for those in need.

In reality, various administrative records indicate that intergenerational mobility in the United States may, on average, be no higher than in Europe. The study showed that Americans are generally more optimistic than Europeans about intergenerational mobility: they tend to overestimate the likelihood of getting into the upper class from “the bottom”. At the same time, they more or less accurately assess the likelihood of staying among the lower class, and the Europeans, on the contrary, overestimate this chance, expressing a more pessimistic opinion.

The researchers wanted to find the link between a view on the need for the redistribution of wealth and ideas about mobility – and they succeeded.

“The more pessimistic people are, the higher the maximum tax rate they want, and the more they want to tax high income. The same goes for health insurance, investment in education, real estate tax, and so on. The more people believe that they can climb to the very top, the more they believe in the American Dream, and the less redistribution they want,” the professor shares the results.

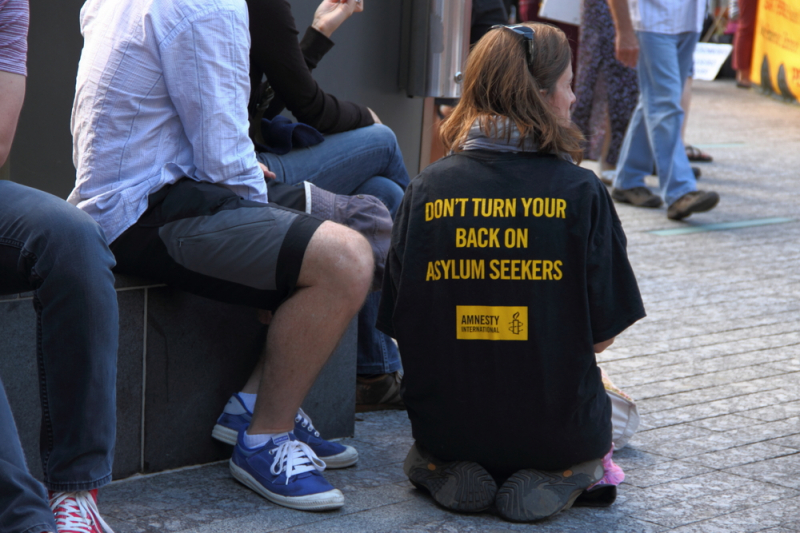

Perception of others through the perception of immigrants

Scientists need to understand people's attitudes towards the results of scientific analysis of economic problems. Stefanie Stantcheva insists that disputes over immigration are often based on misconceptions about the number of immigrants and their role in the economy. In her study, the professor presents data from six countries (the USA, the UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden) on the actual number of immigrants and shows the difference in how people see the situation.

Here, she also stresses one of the perception errors that researchers should pay great attention to: “In all countries, people are prone to exaggerate the number of immigrants. I think that it is connected with our tendency to concentrate on the most obvious and visible. The media has made immigration the most discussed topic. <…> Also, I have not shared these results yet, but people living in areas where there are more immigrants exaggerate their number but, at the same time, they also express less negativity towards them. Probably because they interact more”.

As part of the detailed survey, the researchers also discovered another pattern related to attitudes towards the political situation: if a survey asks people to first think about immigrants and then asks questions about economic policy, they are more likely to support a less progressive and less distributive system.

Tax matters

The third project that the professor talked about was related to how people understand tax policy. This is a new study that aims to uncover the reasons that people take into account when analyzing tax policy. It was about three different factors: distributional, efficiency, and economist's perspectives.

“The first is about who wins and who loses from a certain policy, the second estimates the economic costs of its implementation, and the third combines the first two perspectives and focuses on the need to find a balance between these two forces,” Stefanie Stantcheva explained to Kommersant.

In order to learn what first comes to people's minds when they are asked to think about politics, its shortcomings and goals, the researchers used open-ended questions and then evaluated the data using text analysis methods. There are divergences of varying magnitude and significance not only in people’s final views on politics but also in their reasoning about various underlying mechanisms.

The researcher summarizes the research findings: “What ultimately determines the degree to which people support taxes is their views on equity and redistribution. Then comes an attitude towards the government. People who don't trust their government want the least of everything: fewer taxes, less interference, and less redistribution. Ironically, these are the factors that economists leave outside of standard models.”

The professor also mentioned a fourth project, which is devoted to a deeper analysis of how information about inequality and taxes affects people's perception of redistribution.

On the benefits and methods of surveys

Surveys allow us to see what is not possible to find in official data sets: people’s perceptions, thoughts, attitudes, and principles. According to the professor, they enable researchers to ask people direct and open questions to reveal their motives. They also help predict citizens' acceptance or rejection of economic policies.

“It is especially useful to see what result people expect, what they have already imagined, and how they formed their opinion about what this or that policy will do. This will immediately determine how much they support this decision. Therefore, it is very useful to predict the level of support for certain decisions, the decision-making process, or what needs to be done to fill the gaps in people's knowledge or motivation,” Stantcheva explains.

The researcher and her colleagues experimented with showing short instructional videos that explained how a particular political reform works before asking questions. According to the professor, after watching the videos some respondents may change their minds about particular government policies. Therefore, in her opinion, it is explanations, rather than simple facts, that can be useful as a first step in elevating the policy debate.

“We can develop more effective awareness-raising activities that can really help people better understand the economy, economic policy, and all of these phenomena,” Stantcheva explained to The Harvard Crimson.

The New Economic School has held over 40 public lectures. Besides NES professors, the list of speakers featured Jean Tirole, a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences Laureate; professors from top international universities, including Oleg Itskhoki, a professor at Princeton University, Sergei Guriev, a professor at Sciences Po; and senior business executives such as Dzhangir Dzhangirov, Senior Vice President, Chief Risk Officer of Sberbank Group in Russia, Olga Kotsur, Mercaux founder, and many others.