Under the sea

In 2017, it was claimed that only a fraction of the deep ocean’s area has been explored, which makes it one of the least investigated biomes on the planet. This fact is particularly startling when we think how much we know about outer space – and then consider the similarities between expeditions beyond the Earth’s orbit and into the deepest corners of the oceans. But we do still know something.

First of all, we can imagine life beneath gallons of water as the ultimate slow-motion film: environmental conditions here alter at the pace of geological changes and movement is rather limited due to all the pressure, so most creatures move slowly. But to a certain extent they can afford it: some of the known deep-sea species may live at least several hundred years, while lives of others can exceed 1,000. You wouldn’t really need to hurry when you have all the time in the world, would you? This slow living also manifests in relatively longer reproduction time, which means that these deep-living creatures are highly affected by human impact and any change happening to the global ocean.

The typical life conditions of these deep marine inhabitants can also be likened to outer space: the deeper we go, the darker it gets, so bioluminescence becomes one of the main ways to communicate – which means that the constant darkness is occasionally pierced with “flickers” of slowly moving bodies. If we ignore the difficulties of surviving under extended pressure, we can even consider these environments peaceful and calming. A kind of tiny galaxy hidden right inside our planet.

Surprisingly to those of us who believe that the deep sea is home to giant monsters, it's the smaller creatures who thrive here because they can adapt to limited food resources. So far, it seems rather unlikely that such prehistoric survivors will be discovered in the hadal zone (which is a fancy term for “the deepest layer of the ocean”).

Why so deep?

Advances in underwater exploration have been made with various autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), which are basically tiny submarines launched from a ship stationed at a scientifically interesting location and then controlled remotely from it.

A typical AUV mission would involve first lowering the exploring vehicle and launching it on its mission, usually with the ability to track it down as it is in the water. Then, when the mission is complete, the AUV has to be recovered by using radio-based navigation. As you can imagine, this is not the easiest task to perform and some common problems with such exploration are loss of vehicles due to radio navigation malfunction or difficulty navigating (so that sometimes researchers cannot find the location they have previously visited with an AUV mission before). Moreover, in the Arctic such missions are complicated by a thick layer of ice that at the same time decreases the ability to communicate with the AUV and thus locate it and brings down the main ship’s maneuverability, meaning that AUVs cannot always be picked up timely.

Robots to the rescue

Thankfully, developments in robotics and AI made over recent decades may finally lead us to discover the multitude of underwater organisms still unknown to us, as well as the way to preserve their variability.

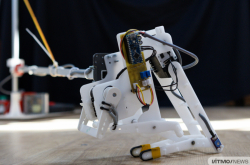

This piece and my renewed interest in the marine world, for instance, was inspired by this soft robot that was made to resemble a snailfish. Rather ingeniously, I think, a group of researchers from China decided to look at the deep sea organisms themselves to come up with a brand-new underwater exploration design. Moving away from using the bulky constructions of typical AUVs, these researchers modeled a robotic snailfish that can power itself with the movements of its “fins” and has been successfully tested in the Mariana Trench – as you might guess, the ultimate test field for all underwater exploration tech. By the way, it was not the first time scientists used marine creatures for inspiration in robotics: check out this article to learn about a soft arm inspired by octopus’ tentacles.

Various ways have also been suggested to make deep-sea cameras more affordable and easy to use (for instance, providing for a live broadcast) by applying 3D printing and using new materials to protect them from pressure. And, naturally, where would we be without machine learning – thus, camera images can be analyzed much more efficiently with a new deep learning algorithm that will first dehaze the picture and then recognize the shapes in it to identify which creature they are most likely to be.

I believe that researchers several decades ago would’ve dreamed of such tech: if we combine all these advances, we get reliable life-like robots equipped with better quality cameras (suited for remote control) that could potentially identify the most interesting objects to look at themselves! Imagine that in a few years we can get fully autonomous robots that would explore the deepest layers of the ocean, finally giving us answers about the most unexplored corners of our incredible planet.

References

Here is a complete list of references so that you can explore all the articles on your own. Enjoy!