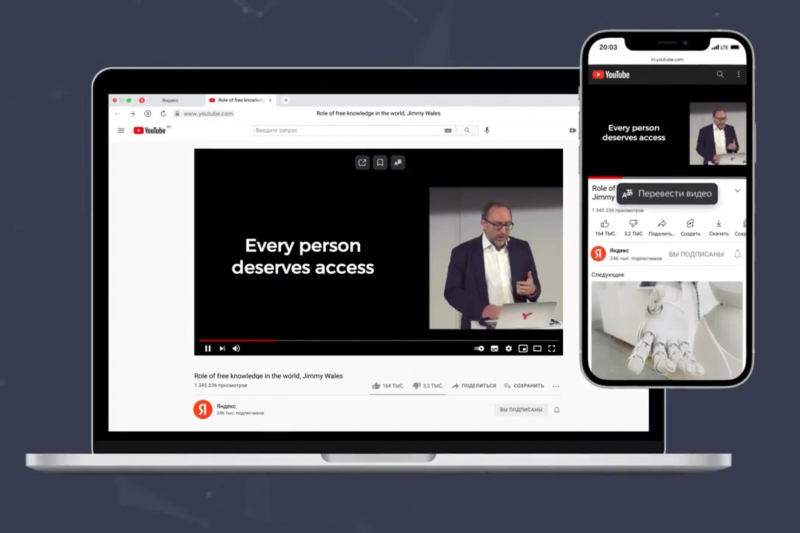

The translation takes up just a couple of minutes: Yandex’s neural networks process the speech, turn it into text, synthesize a Russian translation, and sync it with the video. They are also able to determine the speaker’s sex using biometrics and choose the corresponding voice. At the same time, the characteristics of speech, such as emotions, intonations, pauses, and breakdown of phrases should remain the same.

ITMO.NEWS interviewed Andrey Zakonov, ex-head of Yandex’s Alice and Smart Devices projects, a graduate of ITMO’s Information Technologies and Programming Faculty (formerly, the Computer Technologies Department – Ed.), who came up with the idea for the voice-over translator and launched the project at Yandex.

How did the project start?

I was the head of the Alice and Smart Devices team and this new product was also born there. At first, we created the initial prototype and then began to invite our colleagues from other departments to form a new team. I was a part of it until its pilot launch in July 2021. Now the Yandex.Browser team took over the project and I’m busy with a new initiative in another company. So I can tell you about the product idea and the process of working on it up until the beta launch – I don’t know what’s planned for the project further.

We had been solving similar tasks while working on Alice – we needed to teach it to recognize human speech and do it quickly. In split seconds, it must recognize the speech, process, summarize, interpret it, and understand the question, as well as look for the answer on the web and then share it out loud. The task is very difficult, we’d been working on it for several years and as a result, managed to reach almost real-time communication – it’s pretty much like talking to a human.

Andrey Zakonov

Meanwhile, the Yandex.Translator team learned how to translate from English to Russian and do it well. The neural network doesn’t translate separate words but recognizes the context, phrases, and paragraphs.

So when we started to think about how to develop our technology, I came up with the idea for an automated video translation. Basically, we already had the required technologies: we can recognize text and voice, translate it well, as well as synthesize speech to make it more human-like, emotional, and with correct intonations.

One thing we still had to decide was how to make the tool as convenient for users as possible and develop the final product so that they wouldn’t need to visit a separate website, insert the link, and wait for the result. That’s when the Yandex.Browser team joined us as the browser was the best solution that allowed us to put all our technologies together.

How do you make synthesized speech emotional? How can a machine know which intonation to use?

It’s a rather big issue that we only started to develop. Initially, we wanted to let it repeat the intonations of the original track like professional interpreters and voice-over actors do. The goal is to make the process of watching the video pleasant and comfortable. Emotions, intonations, pauses, and so on must remain in the translation.

You can’t understand emotions through text – it’s the speech that contains irony, sarcasm, joy, irritation, etc. and therefore, we have to use the original track to detect emotions. But this is more like a plan for the future.

Where do the emotions come from: is there a database of all words read by actors with different intonations?

It’s not just about just reading all the words, it’s more complex. Otherwise an actor would have to record all Russian words – it’s an enormous amount of work. Moreover, new words, terms, and names appear all the time. Or take Yandex.Navigator for instance – there are countless names for villages, streets, toponyms, etc.

That’s why we do it another way – we use phonemes or even their fragments and then form words and sentences out of them. Emotions are also added during the postprocessing. One and the same phrase can be generated with different emotions, as well as with different speed to make it fit the sound of the video – this is also done during the postprocessing.

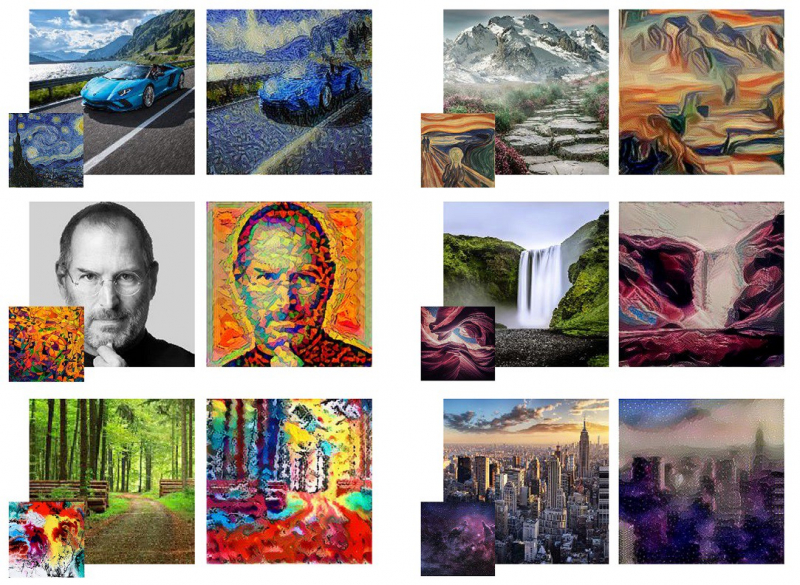

Style transfer technology. Credit: Thushan Ganegedara / Towards Data Science

Take style transfer technology, for example – it’s very popular in the field of image processing. Any photo can be turned into a painting similar to that of Van Gogh or Salvador Dali through a certain style superimposed on the image. You can do a similar thing with voice: it’s possible to train models on a dataset with phrases spoken happily or sadly and end up with the ability to transfer a certain emotion to synthesized speech. This is a very interesting field of speech technology, but so far it’s only starting to develop.

How is biometrics involved in the voice-over?

In the current version, biometrics is used only to detect the sex of a speaker and choose a male or female voice. The next step is to add more types of voices and teach the model to distinguish them. Each voice, like a face, is unique and has recognizable characteristics.

We launched an interesting related feature in our smart speakers: Alice understands if a child is talking to it and automatically introduces age restrictions, chooses funnier answers, and is less formal.

Are there any challenges that are yet to be solved?

I experimented a lot with different videos. There are genres where this technology doesn’t perform adequately yet. It works well when one speaker presents something in a lecture format or several speakers talk in an interview. But it works worse if there are a lot of slang words or emotions. For example, the now popular genre of video game streaming often involves a lot of specific words and harsh incoherent cries. Or some vlogs where people tend to speak very emotionally.

It also doesn’t work well when several people talk at the same time. The translation will be read out loud in one voice, so several speakers will blend into one.

How come this technology appeared in Russia? Why haven’t major IT corporations come up with it before?

There are many factors. Firstly, in English-speaking countries, this technology is less in-demand because there is much more content in English than in any other language. Secondly, now is the right moment for such a technology to appear. Five years ago, there was significantly less user-generated content. Ten years ago, there was no need for such a tool because most of the video production was professional, which involved a lot of money, so a professional translation was also provided.

Nowadays, thousands of great videos in various languages appear daily and it’s impossible to translate them quickly and inexpensively. It’s a time-consuming and complex task.

In Russia, there’s a great demand for English content. I’m personally interested in educational information for the most part, and in any field, be that IT, art, or something else, there’s much more content in English.

At the same time, about 5% of the Russian population can speak English freely, according to the Russian Public Opinion Research Center. So a few people are able to listen to a Harvard or Stanford lecture without translation. Subtitles aren’t the best option either – it’s much more pleasant to listen to lectures with voice-over translation.

Here’s another important thing – it takes lots of technologies to create such a tool from scratch. You need voice recognition, synthesis, biometrics, and translation. Luckily enough, Yandex already has all of these. Moreover, they are in use and ready to be applied at full capacity. There are few companies in the world with such a developed set of technologies.