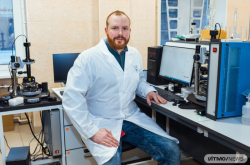

What can you tell us about your field of work and scientific interests?

My field of work is interdisciplinary. I started out as a theoretical physicist in condensed-matter physics, but I applied it to optics and semiconductor systems that are used to create lasers, which are actively used in the industry. In particular, I was working on a theoretical design of a new type of lasers called “polariton lasers”. However, since quantum optical systems have other peculiar properties, like the ability to store quantum information for a long time and to process it very quickly, I grew more interested in quantum computing and shifted towards theoretical physics in that area. In the recent years I’ve been working towards creating a quantum computer with the resources that we currently have.

What are your thoughts on the perspectives of quantum computers in the coming years?

Today’s quantum computers do not yet have the power that was expected of them, and it is still necessary to teach them to correct their mistakes. However, what we can do with quantum computers is simulate quantum systems. Scientists have already managed to preserve the quantum state of numerous atoms or photons; with just a hundred of such particles, called qubits, it is possible to perform some really complex calculations. I believe that in five years physicists will demonstrate the ability of quantum computers to perform calculations that are impossible on classical computers. Becoming a fully functional industry and making profit is another matter and I think this will take them about 20 years, since it is a really slow process.

Are there any businesses that are already working with quantum computing? As a scientist, have you had any contact with them?

Projects are usually commercialized in the early stages, and lately there have been a lot of startups that have to do with quantum computers. The idea is that in five years they will be used to solve specific tasks of quantum chemistry and in twenty years they will already be dealing with optimization-related issues. It will take a lot of time for us to learn how to use them, which is why these startups suggest that we should be writing the code for these computers and testing it on simple tasks right now. My job as a theoretical scientist is to bring forward new physical solutions for the operation of the computers. The gap between the academic world and the industry is getting smaller and smaller, and in due time it will cease to exist; even now the conferences on quantum computing consist of 75% industry and startup reports and 25% academic reports. Startups will gradually shift from R&D towards more pressing issues, like the compilation of code, computer architecture, protocols, etc. Some scientists are also gradually shifting from purely scientific work to startups without changing their research topic.

What is the work of a theoretical physicist like? How does it overlap with experimental physics?

In my work, theoretical and experimental physics come together; despite the prevalence of computation, I always keep practical applications in my mind. The abovementioned lasers and quantum computers are a great example of that. My typical workday consists mostly of calculations, of course. Some of them can be done with just pen and paper, but very often there is a need to use high-level programming, or even multicore cluster computers if I have to simulate quantum systems. But my favorite part of the process is the thinking. However obvious this might sound, theoretical physicists must think a lot. It is a difficult thing to describe, but the problems are in your head all day long, and solutions may come to you at any time. That’s when you grab your notebook, write it down, check it later with some simulations. After an idea is formulated, a long and meticulous process of working the task begins. Will it work with an existing experiment? Is there a need for a new setup? Can anything be done better? Therefore, in specific smaller cases there is a real possibility for “eureka moments”, but in order to achieve them one must reflect on the problem for a very long time. It can take days or even longer than that. Some projects stall for years simply because there are no ideas for them. Then, at some point you visit a conference or read a paper that might be completely unrelated to the task at hand and yet provides you with the right solution.

What part of your work brings you the most joy?

Theoretical physics is different for every scientist. Part of the enjoyment comes simply from the fact that the suggested method works. But it is not enough to motivate myself; I want there to be a practical application. This can be either an experiment that follows my model or the recognition from the academic community: the fact that my algorithm will be perfected by others, that my knowledge will be preserved and propagated is what I would consider to be the most pleasant aspect of my work.

A crucial part of every scientist’s career is publication activity. Your papers regularly appear in well-known journals like Physical Review Letters, and this September you had a paper in Nature Communications. Could you share your experience in publications, as well reviewing other scientists’ papers?

The view towards publications changes with time. For a student getting his Master’s Degree or a young postgraduate student, every single paper takes a lot of effort, not only technical and professional, but also personal, because the modern publishing process is very complicated. Your paper may sometimes get negative reviews, and what’s worse, they’ll often not explain their reasoning clearly. I would advise everyone to not take it too personally, because every paper will eventually be published. Do not be afraid of famous journals with high impact factors; always go for it, because you won’t know the quality of your work until you try. As for all the technical aspects of writing a good paper, like choosing an interesting style that will also be well-received by the scientific community and answering to the editor in a manner that gets your paper published, they come with practice, so a scientist must write a lot. When I perform my duty as a reviewer, I always follow the reciprocity principle, i.e. if I want to receive thoughtful reviews on my papers, I must write them with the same quality. It is never enough to simply state that you do not like the paper. Instead, you must explain why it does not fit this particular journal. I always try to point out some ways that the authors could rewrite their paper so as to better demonstrate its scientific merit. Common mistakes include incompetent descriptions of the results, in which case the authors should provide some additional data. There are cases, however, where authors conceal their results, for example, by using unrealistic parameters. In this situation a good reviewer must perform the calculations on their own and then tell the authors that no device in the world would work in such conditions. A paper like that would be rejected by any journal.

Tell us a bit about your career. How did you pick the place to get your PhD?

I finished by Bachelor’s and Master’s Degree at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. To a certain extent, my career after that has to do with chance. Searching for a postgraduate degree means sending out applications for certain positions, and my goal after Kyiv was to find a place that would allow me to continue my current studies, as well as to master new scientific fields. I applied for positions in the USA, France, Germany and at some point saw an opportunity in Iceland. In case of the USA, the application process depends greatly on the university you pick. It is a tedious procedure that takes up to a year and often doesn’t let you communicate directly with your advisors, only with various committees. On the other hand, in Europe, you can get your answer relatively quickly and start working in a couple of months. When I received an offer from Iceland, I found the topic very interesting, so I read a little bit about the country and decided to move there.

After Iceland you worked in Denmark and then Sweden. What made you choose Scandinavian countries? How much do they have in common?

Unlike Iceland, Denmark was chosen after a careful search. I had other opportunities, such as Austria, but during my time in Iceland I came to love living in Scandinavia. Despite the vast differences in weather and landscape — the highest point in Denmark is a basically a hill that is 170 meters high, whereas Iceland is a country of ice and volcanoes, where you feel yourself as though you are on Mars — they are very similar in lifestyle. It is a society that values independence, comfort and convenience, but at the same time is very secluded. The further you move to the south of Europe, the more people communicate with each other. The manners in Scandinavia will differ significantly from those in Spain and also from those in Russia. For instance, it is pretty much always considered rude to talk to strangers on the street.

I also worked in Singapore for two years as a part of my postgraduate studies. It is completely different from anything I’ve ever seen before. First of all, there is an opportunity to spend a lot of time outdoors: even though it is a megalopolis, there are a lot of national parks there. Also, it has great connections to other countries of Southeast Asia. If you ever have the chance to visit Singapore, you should take it, because from there you can fly to Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Indonesia with little expense and a lot of new experiences. These countries have inexpensive housing, delicious cuisine, and are very safe to visit. People there are extremely friendly.

How did you find out about the Fellowship program and what brought you to Russia?

I learned about the program a long time ago, and I have a lot of experience in collaborating with scientists from ITMO University. To me, ITMO is an example of how real innovations can take place in Russia and how science can be transformed into something useful. I decided that in order to make my collaboration more productive, I can just visit the university and work here, which is why I applied to the program. I haven’t seen much of Russia besides central St. Petersburg yet, so I don’t really see much difference from, say, Stockholm. Still, living in Russia feels like a new experience to me and I would like to travel around the country to get to know it better.

Tell us more about the different educational systems that you have seen in your travels. Is it different in Scandinavia, Singapore, Russia?

In Scandinavia, the approach towards education is such that even while the student is not on the same level as the teacher, they can always ask any kind of question; there is no gap between them. There is also a new tendency for some young people to skip university because they don’t feel the need to go there: if you choose a profession that does not require a degree, you don’t waste time getting one. At the same time, such professions are also greatly respected in the society, and those who still decide to go to the university arrive there prepared and with a great high-school education.

In Singapore, education is fee-based, like in the UK and the USA, and sometimes entire families pay for the education of their children or take on loans. I haven’t yet had the opportunity to examine the educational system in Russia, but here at ITMO University I have seen a shift towards a larger degree of interaction between students and their teachers, and there is a noticeable replenishment of the teachers themselves — there are a lot of young specialists giving lectures. Another important feature is the introduction of brand new courses in the University: even though classical theoretical physics should definitely be taught in the first years, the students also have an opportunity to study more specific disciplines and real cutting-edge science. I believe that the decision to incorporate Digital Culture as a subject for all Master’s students is a great one.

What are your plans? Where do you plan on going next?

Modern science is very dynamic, which is why I wouldn’t really try to make very specific plans. I know that I definitely want to work on quantum computing, whether that would be science or business, as there are a lot of opportunities in both of these fields. What really matters is an interesting topic and proper funding; the country of residence is not that important. Not everyone can follow this path: some people choose a specific country or city and then do not manage to find work there. If you choose to be a theoretical physicist, be prepared to travel a lot and choose a position with a challenging and fulfilling research. There are people from all sorts of countries among my collaborators, and the definition of “nationality” sometimes fades away. In this field one can truly be “a citizen of the world” and not be bound to anything but physics.

What advice would you give young scientists? Are there any important trends that you can note?

One current global trend is that young people no longer have to wait for a long time to make significant contributions to science, business or technology. With time, a person’s age will start to matter less and less. I would advise all the young specialists and students that are thinking of a career to go for it as soon as possible. If you have always dreamt of being a scientist in a certain field or applying to a certain university or even starting a business, try to do it sooner rather than later. If you try hard, at some point it will take off. You should never lose heart and work gradually and diligently towards your goal.