How did you get into accelerator physics?

To be honest, it was pure chance. I got my Master’s degree in quantum mechanics from St. Petersburg State University and became a researcher at the Russian State Scientific Center for Robotics and Technical Cybernetics. Back then, I wanted to develop AI, but unfortunately a PhD program in the field was only available in Moscow. I didn’t want to move – I was in a rock band and didn’t want to leave my friends. Dima Semikin, who played the bass in our band, was a PhD student at LETI University and he recommended that I reach out to Alexey Kanareykin, who became the supervisor of my PhD thesis. He studied classical radiation, had many ongoing projects, and headed a small research group that included Ilya Sheinman and Alexander Altmark. They worked with the theory of accelerator physics – and that was how I got into it, too. As a result, I defended my PhD thesis on the topic at the Radiophysical Council of St. Petersburg State University.

After getting my PhD degree, I spent 1,5 years as a postdoc at the American research company Euclid TechLabs, which specializes in linear particle accelerators. Afterwards, I became a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Chicago, where I worked at The Center for Bright Beams for almost three years. After that, I had to look for another position and, thanks to my previous experience, I landed a job as an assistant professor at Northern Illinois University.

In the US I kept expanding my knowledge in the field of accelerator physics, especially in the related theory, as I found it more interesting. Many of my colleagues say that accelerator physics is an experimental science, but I completely disagree. Physics is a synergy of theory and practice – we can spend a long time theorizing but if we can’t prove it experimentally, these theories won’t be more than fantasies. On the other hand, we can look for various phenomena, but without an understanding of what we are looking for and where, experimental physics would be fruitless. It’s not about there being theoretical and experimental physics, but just physics and a question that we want to answer. In order to do that, we pick the right tool, be that computer simulations, experiments, or analytical calculations.

University of Chicago. Credit: depositphotos.com

You were offered postdoc positions at Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago, but you opted for the latter because you prefer the university environment. Do you feel universities in the US and Russia are different in this respect?

Surprisingly, there are essentially no differences. Of course, there are some if we are talking about a classical Soviet university, but as for contemporary Russian universities, they are not that different from those in the US: in both countries, professors propose projects, read lectures, and develop their specific research fields. Grants go towards salaries for students and development of labs, while professors themselves are paid by universities. Apart from summer months, which can be covered by small parts of grants.

I think that the main distinguishing feature of American universities is that they can secure collaborations with industrial partners and they see value in that. Even researchers engaged in fundamental studies always think of ways to implement at least part of their work in collaboration with a company. I like this approach and it used to be unimaginable in Russia, but we are gradually establishing such partnerships

What did you gain from working in the US?

First of all, I learned what it was like to work in an environment where you have no support, you are treated neutrally, which means you have to build your reputation on your own from the ground up. In order to earn attention and respect for your research, you have to work really hard. It’s different in Russia – you are welcomed more warmly if you graduated from a good university. I also gained experience of working independently, I learned to set tasks and think critically.

One other thing is that I realized that science doesn’t depend on where it is conducted, but on who does it. It doesn’t matter if we are in Europe, Russia, or the US, but the people are important. These days, the kind of funding that goes into research makes it possible to say that there are fields that are flourishing. It used to be unclear where to find the necessary equipment for research, but now we have it or can create it. I always thought that it was better in the US. I left for the country believing that Russian science is going down while it’s burgeoning across the pond. However, in the US I discovered that researchers there also face challenges and there is no miracle. In order to be successful there, you have to work harder than I did during my PhD studies, and the secret to success is first and foremost in focusing on your goal and determination. I realized that everything is in my own hands and it doesn’t matter what country you work in – it matters what your goal is and who is around you.

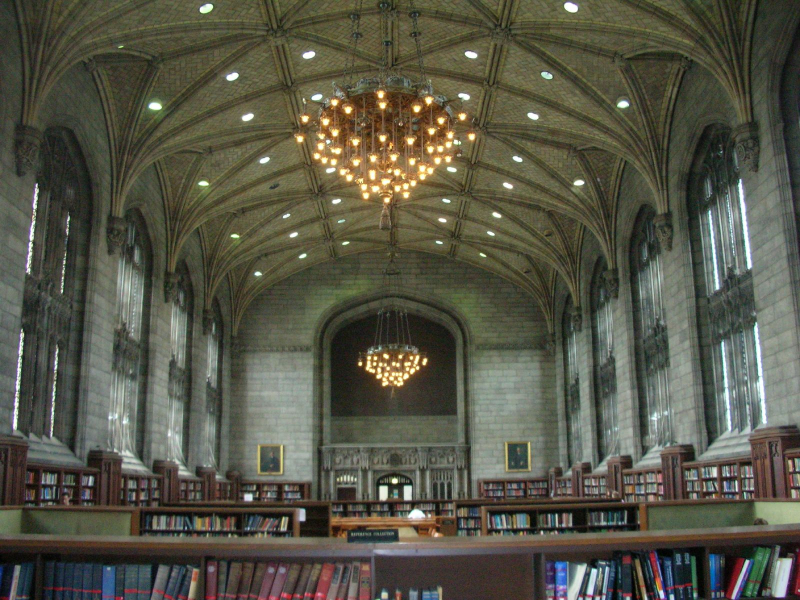

Harper's library, University of Chicago. Richie D. originally posted to Flickr as One of the Several Libraries, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

When I was a student at St. Petersburg State University, I felt that I am following in the footsteps of great scientists who carved out contemporary science. For instance, the Department of Quantum Mechanics was founded by Vladimir Fock, a famous 20th-century theoretical physicist. I felt the same way at the Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics and the P. L. Kapitza Institute for Physical Problems in Moscow. Many well-known scientists worked at the University of Chicago, but the most famous one was Enrico Fermi, who built a nuclear reactor right at university. It was exciting to be that close to history. Moreover, I am a great Indiana Jones fan and at the University of Chicago I got the chance to visit the room where the titular character gives his lecture in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Such things mean a lot.

When you came back to Russia, you applied for ITMO’s Fellowship & Professorship program. Why did you choose ITMO?

I met Dmitry Karlovets before joining the program, and he told me about this opportunity. We discussed a potential joint project with him and it turned out that part of it was connected to something I was already doing, and the other one had to do with something I wanted to try – so our Fellowship project appeared by itself.

When I started to get to know ITMO’s Faculty of Physics, I was amazed by its atmosphere and the spirit of true science. I haven’t seen so many people who want to do science in any other one place. I am really happy and proud that researchers here give their all to their work. It’s a pleasure to see such universities in Russia.

Stanislav Baturin at an ITMO Fellowship & Professorship event. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

As part of the program, you collaborate with Dmitry Karlovets on a project about particle physics. What other projects are you engaged in at ITMO?

My responsibility in the project is to bring to life all the ambitions and ideas developed in the field of physics of spinning particles at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research. We currently know how to spin low-energy particles, but it’s less clear with high-energy ones. That’s why we want to develop a method and a technology and later conduct experiments with a linear accelerator and other installations available in Dubna. It’s interesting to accelerate such particles at least because spins add an additional degree of freedom that can significantly affect particle interaction. As not all reactions can take place in low-energy conditions, the accelerator will be an important tool for testing our theory and potentially looking for new phenomena outside of the standard model.

Even though I am responsible for experiments in the Moscow Oblast, I am still engaged in theoretical work. For instance, in collaboration with Andrey Volotka we are outlining the effect an atom’s spin can have on its electron spectrum, the atom’s microstructure, and whether the electron interacts with the orbital moment of the atom as a whole. If the spin has an effect on the microstructure, then the splitting of electron levels has to occur analogous to that observed in the magnetic field (the Zeeman effect). If the microstructure remains unchanged when spinned, then it indicates the existence of a universal law that works not just for electromagnetic particle interaction, but the other kinds, too.

ITMO's delegation at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR). Photo by Elena Puzynina, JINR

You and Dmitry Karlovets are also planning to organize an optional course on megascience-class installations. What is it about and who is it meant for?

It’s something like a review of the experiments and fields that are currently developing all over the world. We understand that contemporary physics, both experimental and theoretical, has become very complex and the most deep and exciting questions require a lot of effort. That’s why we create those giant installations. Each of them, such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the laser installation LCLS, and the upcoming NICA accelerator in Dubna, is a unique and advanced machine that helps us find answers to specific fundamental questions. In the course, we will talk about the principles and ideas at the core of such machines, as well as the tasks researchers are trying to solve with their help. We will have to start with the very basics for some of the topics, so this course is suitable for everyone, from Bachelor’s students to postdocs – you will only need a general background in physics. We want to introduce as many people as possible to contemporary scientific trends. We want them to stop being afraid of science and be able to chuckle at the next dramatic headline that says the LHC will create a black hole and destroy us all.

There will be eight classes that you will have to sign up for in advance. The course will start on March 11 and run till mid-June. Classes will be in-person and will take place at ITMO’s Faculty of Physics. Recordings will also be available. Having successfully passed the final test, ITMO students will be able to include the course in their diplomas as an optional one. Other listeners will get a certificate of completion.

Stanislav Baturin. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

My lectures will focus on wakefield acceleration: I will talk about the benefits and challenges of this method, the main ideas and physical foundations behind it, and the examples of contemporary installations that rely on it. Dmitry will share information on why we create new installations in the first place and which areas of physics remain unexplored.

How do you spend your free time?

I love making music – I can play the guitar and bass and I used to have a rock band; we even recorded our own tracks. I also love running, but it’s hard to do it in the winter because of the snow. I would love to be able to say I love reading, but to be honest, I am not much of a reader. Luckily, my wife compensates for it by retelling me all the latest releases. I try to spend more of my free time with my kids.